Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

Testis size and breeding

system

The heaviest primates, the gorilla (

Gorilla

gorilla

) and orang-utan (

Pongo pygmaeus

)

have breeding systems that involve one

male monopolizing mating with several

females, and have testes that weigh

30 and 35 g, respectively (average weight

of both testes). The smaller chimpanzee

(

Pan troglodytes

), by contrast, has a

breeding system where several males

copulate with each oestrus female and

this species has testes weighing 120 g! It

seems likely that the marked differences

in testes weights are related to differences

in breeding system. In single-male

breeding systems (gorilla and orang-

utan) each male needs ejaculate only

enough sperm to ensure fertilization.

In multimale systems (chimpanzee),

however, a male's sperm has to compete

with sperm from other males. Selection

should, therefore, favour increased sperm

production and, hence, larger testes.

Harcourt

et al

. (1981) tested this

hypothesis by comparing 20 genera of

primates, varying in body size from the

320 g marmoset (

Callithrix

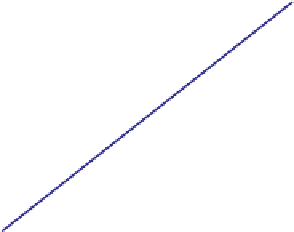

) to the 170 kg gorilla. Figure 2.7 shows that, as expected,

testes weight increases with body weight. For a given body weight, however, it is clear that

genera with multimale breeding systems have heavier testes than genera with single-male

or monogamous breeding systems. The data points for the former group lie above the line,

and those for the latter lie below ('single-male' indicates that there is only one breeding

male although, as in the gorilla, there may be more than one male in the social group;

'monogamous' indicates that there is just one male and one female in a group). These data

therefore support the sperm competition hypothesis.

250

100

+

10

1

0.2

1

10

100

200

Body weight (kg)

Fig. 2.7

Log combined testes weight

(g) versus body weight (kg) for different

primate genera. Solid circles are

multimale breeding systems. Open

circles are monogamous. Open

triangles are single-male systems (one

male with several females). The cross is

our own species,

Homo

, for

comparison. From Harcourt

et al

.

(1981). Reprinted with permission from

the Nature Publishing Group.

Larger testes in

multimale groups

Using phylogenies in comparative

analysis

Since the mid 1980s, there has been a further major advance in comparative analysis.

This is to use phylogenies, firstly to identify independent evolutionary transitions and,

secondly, to elucidate the order in which traits have evolved (Felsenstein, 1985; Grafen,

1989; Harvey & Pagel, 1991). Before we describe

how

this is done, we must first expand

on

why

it needs to be done.