Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

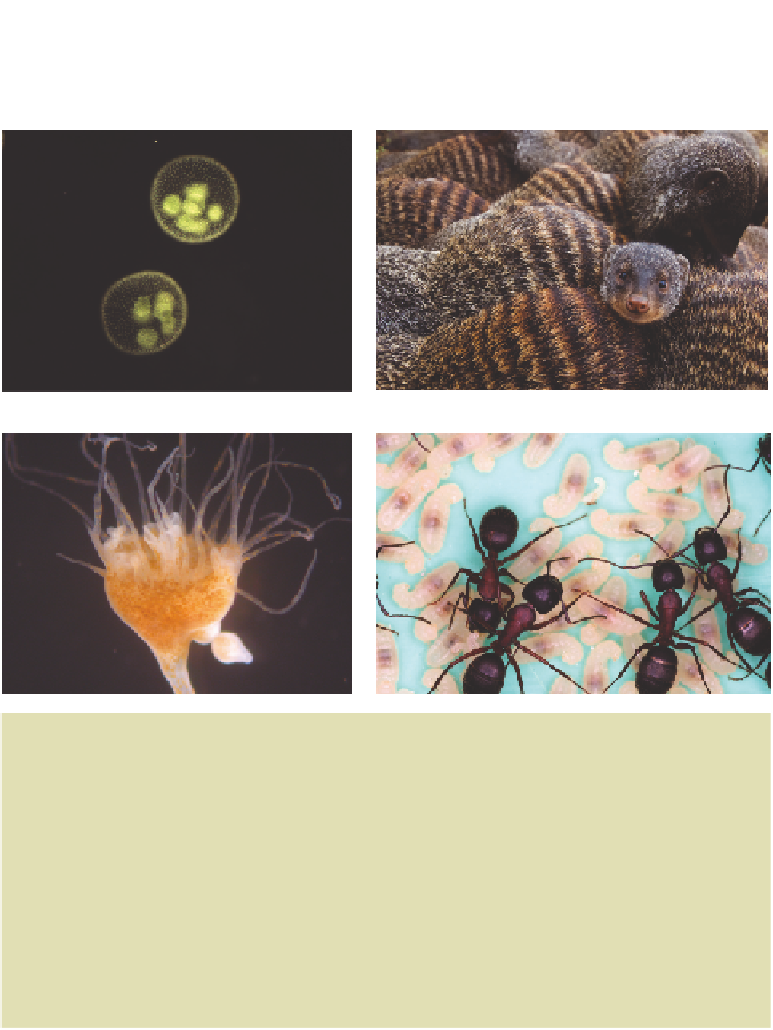

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Fig. 12.1

Cooperation. (a) Cells of the algae

Volvox carteri weismannia

form cooperative

spherical multicellular groups, which contain up to 8000 small somatic cells arranged at the

periphery and a handful of much larger reproductive (germ) cells. This distinction between

somatic and reproductive cells is analogous to that between workers and reproductives in

the eusocial insects. Photo © Matthew Herron. (b) Banded mongooses (

Mungos mungo

)

live in cooperative mixed sex groups of about 7-50 individuals across a large part of East,

Southeast and South-Central Africa. Photo © Andrew Young. (c) An upside-down jellyfish

(

Cassiopea xamachana

) infected with its algal symbiont (

Symbiodinium microadriatum

).

The algae (orange in the photograph) provide the jellyfish with photosynthates in exchange

for nitrogen and inorganic nutrients. Photo © Joel Sachs. (d) In social insects, such as this

ant species

Camponotus hurculeans

, some individuals give up the chance to breed

independently and instead raise the offspring of others. Photo © David Nash.

useful to think of this as cooperation, as the elephant produces dung for purely selfish

reasons (emptying waste). The production of dung would only qualify as cooperation if

a higher level of dung production had been favoured, because of the benefits to dung

beetles. The definition of cooperation therefore includes all altruistic (

A behaviour is

cooperative if it

benefits another

individual and has

been selected for

because of that

benefit

−

/

+

) and some

mutually beneficial (

) behaviours (Box 11.1).

Cooperation can take many different forms in different organisms (Fig. 12.1).

In cooperative breeding vertebrates, such as meerkats or Florida scrub jays,

individuals often live in groups that include the dominant pair, which do most of the

breeding, and the subordinates who help care for the young (Hatchwell, 2009;

+

/

+