Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

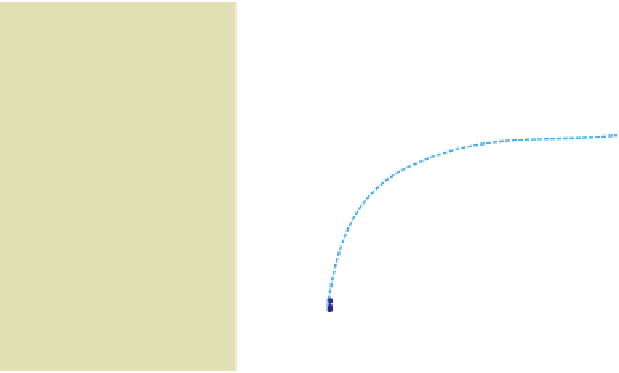

0.75

Fig. 10.4

Sex

ratio adjustment

in the parasitoid

wasp

Nasonia

vitripennis

. A less

female-biased sex

ratio is produced

when larger

numbers of

females lay eggs

in a patch. From

Werren (1983).

Photo by Michael

Clark.

0.50

0.25

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Number of foundresses

males will be wasted. The crucial difference between this and the earlier argument for a

1:1 sex ratio is that here the ratio of males to females in the rest of the population does

not matter. A female-biased ratio within a brood will not give other parents a chance to

benefit by concentrating on sons. Hamilton noticed that in many species where there

was a high likelihood of inbreeding there was a tendency to produce just one or a small

number of males in each brood. An example which supports this prediction is the

viviparous mite,

Acarophenox

, which has a brood of one son and up to 20 daughters.

The male mates with his sisters inside the mother and dies before he is born.

Hamilton also suggested that if individuals could assess the likely degree of LMC that

their offspring would experience, then they should adjust their offspring sex ratio

accordingly. Specifically, if N mothers lay eggs on a patch, and mating then occurs

between these offspring, before only the females disperse, then the evolutionarily stable

(ES) sex ratio (proportion sons) is (

N

− 1)/2

N

. This predicts that the sex ratio should

vary from 0.5 for large

N

(Fisher's case) to increasingly female biased as

N

is reduced.

In the extreme, if

N

= 1, then a sex ratio of zero is predicted, which is interpreted to

mean that the mother should produce just enough sons to fertilize her daughters.

Jack Werren (1983) tested this prediction with the parasitoid wasp,

Nasonia vitripennis

,

which lays its eggs inside the pupae of flies such as

Sarcophaga bullata

. In this species, the

winged females mate with the wingless males, either in, on or near the host pupae in

which they developed, before only the females disperse. Consequently, if only one female

parasitizes the pupa or pupae in a patch, her daughters are all fertilized by her sons and

as predicted the sex ratio of her clutch of eggs is highly biased towards females. Only

8.7% of the brood is male. If more females lay eggs on the patch, then the extent of LMC

is reduced and they should lay a less female-biased sex ratio. Werren found this pattern

in laboratory experiments, with individuals producing a less female-biased sex ratio

when more mothers laid eggs on a patch (Fig. 10.4).

Since then, recent advances in molecular methods (microsatellite markers) have been

exploited to examine whether the same pattern also occurs in natural field populations,

examining wasps that emerge from fly pupae found in birds nests. Max Burton-Chellew and

colleagues (2008) genotyped all the wasps emerging from a number of nests (the offspring),

reconstructed the genotypes of their mothers and hence determined how many mothers

As more females

lay eggs on a

patch, a less

female-biased sex

ratio is favoured.

Parsitoid wasps

adjust the sex of

their offspring,

depending upon

how many

females are laying

eggs in that patch