Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

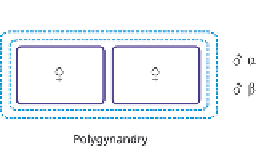

(a)

Monogamy

♀

5.0

♂

5.0

♂

a

♂

♀

♀

♀

3.8

♀

3.8

♂

7.6

♀

6.7

♂

a

3.7

♂

b

3.0

Polygyny

Polyandry

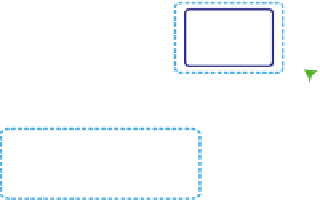

(b)

Fig. 9.12

Male dunnock feeding a brood of chicks. Photo © W. B. Carr. (a) Sexual

conflict in dunnocks. Female territories (solid lines) are exclusive and may be defended by

one or two unrelated males (dashed lines). The numbers refer to the number of young

raised per season by males and females in the different mating combinations (maternity

and paternity measured by DNA fingerprinting; Burke

et al

. (1989)). Arrows indicate the

directions in which dominant (alpha) male and female behaviour encourage changes in

the mating system. A male does best with polygyny; the cost of polygyny to females is

shared male care. A female does best with polyandry; the cost of polyandry to males is

shared paternity. (b) Polygynandry as a stalemate to the conflict: the alpha male is unable

to drive the beta male off to claim polygyny, and neither female can evict the other to

claim polyandry. From Davies (1989, 1992).

Various factors influence the conflict outcome. Firstly, differences in individual

competitive ability are important. For example, young males are more likely to be

subordinate males and older, experienced, males are more likely to defend larger

territories which can encompass two female territories (polygyny or polygynandry).

Secondly, the adult sex ratio influences mating systems; after harsher winters the

breeding sex ratio is more male-biased (females are subordinate at feeding sites and

more likely to die), so there is more polyandry. Thirdly, territory characteristics can

influence the conflict outcome; on territories with denser vegetation, a female can

more easily escape dominant male guarding and so promote mixed paternity

(Davies, 1992).