Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Time (days)

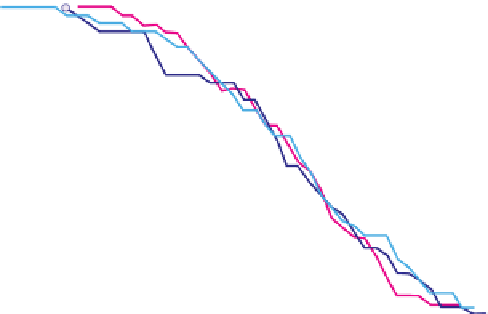

Fig. 7.20

In this experiment, female fruit flies

Drosophila melanogaster

were given

varying exposure to male accessory gland proteins (Acps) at mating, while keeping

constant other costly aspects of reproduction, such as egg production, non-mating

exposure to males and rate of mating. Females exposed to males which produced Acps

(dark blue line) died significantly sooner (median lifespan 21 days) than females exposed

to three other types of males (median 29 days), namely: males genetically engineered to

lack Acps (red line), and two control groups of males (open symbols and pale blue line)

which courted females at the normal rate but could not mate because their external

genitalia were ablated. From Chapman

et al

. (1995). Reprinted with permission from the

Nature Publishing Group.

have been investigated by producing males genetically engineered to lack them or

overexpress them. Among their functions are: incapacitating rival male sperm;

protecting a male's own sperm from enzymatic attack in the female reproductive tract;

increasing a female's egg laying rate; decreasing a female's propensity to remate. All

these will help to increase the male's reproductive success, but experiments have shown

that these male benefits can be at the expense of female fitness because they reduce a

female's longevity (Fig. 7.20). The deleterious side-effects to the female may arise

because the Acps enter the female haemolymph through the vaginal wall and then

perhaps interfere with essential enzymatic processes inside the female body cavity

(Chapman

et al

., 1995, 2003).

Strategic allocation of sperm

. Comparative studies of many taxa (primates, bats, other

mammals, birds, frogs, fish and various insects) have shown that testis size relative to body

size (a measure of investment in sperm) increases with the degree of female promiscuity

(a measure of sperm competition; Wedell

et al

., 2002). The potential for evolutionary

change is revealed by selection experiments with male dung flies; when exposed to

increased sperm competition, larger testes and ejaculates evolved within ten generations

(Hosken

et al

., 2001). These results show that investing resources in sperm production is

costly and evolves only when this brings a competitive benefit. Within species, too, it is clear

that males do not have limitless potential to copulate (Dewsbury, 1982). For example, male