Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

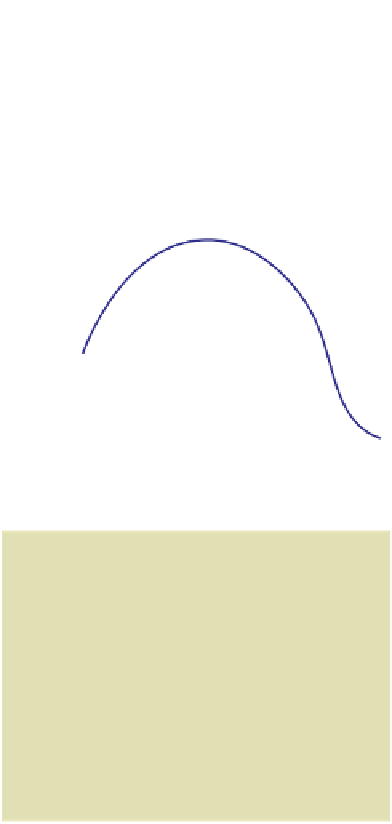

The exact outcome depends on the

shape of the curve in Fig. 6.19, and it is

possible to draw fitness curves which

will result in a stable optimal group size

(Giraldeau & Gillis, 1985).

The general point from Sibly's model

is that unless groups of optimal size

can prevent further newcomers from

settling, groups in nature will often be

larger than the optimum because it will

pay individuals to join groups until a

stable distribution is achieved.

Individual differences

in a group

Skew Theory

Fig. 6.19 considers average individual

fitness in groups of different sizes.

However, in most groups there will be

individual differences in the net benefit

from group living. In foraging flocks, for

example, individuals at the front of the

group may do better than those at the

back (Major, 1978), and when a

predator arrives individuals who can get

to the centre of the group will be safer

than those at the edge. Often older,

larger or more experienced individuals

will commandeer the best positions and force others to settle for poorer places in the

group. In theory, subordinate individuals will put up with lower pay-offs so long as they

could not do better by moving elsewhere. This idea forms the basis of what has come to

be known as 'skew theory' (Vehrencamp, 1983).

Skew models consider the effects of group size on individual reproductive success,

which will be the outcome of all the potential costs and benefits of group living,

including foraging and protection from predators. One possibility is that dominant

individuals have complete control of reproduction in the group. In this case, if a

subordinate tries to take too great a share of the reproduction, to the detriment of the

dominant, then the dominant can do something about it, such as evict the subordinate

from the group. As a consequence, subordinates may restrain their reproduction to

avoid eviction by the dominant. Alternatively, if dominants do not have complete

control, there may be 'tug of war' conflicts over reproductive shares.

This is a topic where empirical studies have lagged behind a proliferation of theoretical

models (Keller & Reeve, 1994; Reeve, 2000; Johnstone, 2000; Kokko, 2003). We shall

consider two studies of how grouping is maintained despite a skew in benefits within

the group.

1

7

14

Group size

Fig. 6.19

Optimal group sizes may not

be stable. In this example individual fitness

is maximal at a group size of seven, but a

new arrival would do better to join this

group than to be solitary because

individual fitness in a group of eight is

higher than in a group of one. Further

individuals should continue to join until the

group size is 14. Only after this would the

next newcomer do better alone. After

Sibly (1983). With permission from Elsevier.

Individual

differences in

benefits: who is in

control of skew?