Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

grouping provided attack rate

does not increase propor-

tionately with group size; if a

group of N individuals suffer N

times as many attacks as a

singleton, then clearly individuals

will be no safer in a group than on

their own. However, if there are

less than N times as many attacks

at a group of N, then individuals

will still be safer in a group. The

key point of this idea is that even

when there are no other

advantages from grouping, for

example better detection of

predators or communal defence,

individuals will often still be safer

in a group through dilution of the

risk of attack.

100

10

Predicted

1

Observed

0.1

0.01

1

10

100

Number of water skaters in the group

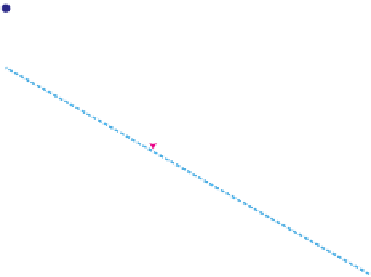

Fig. 6.2

An example of the dilution effect. The

prey are insects called water skaters (

Halobates

robustus

) that sit on the water surface; their

predators are small fish (

Sardinops sagax

). The

fish snap the insects from below, so there is little

possibility that vigilance increases with group size.

The attack rate by the fish was similar for groups

of different sizes, so the attack rate per individual

varies only because of dilution. The 'predicted'

line is what would be expected if the decline in

attack rate with group size is entirely caused by

dilution; this line is very close to the observed.

From Foster and Treherne (1981). Reprinted with

permission from the Nature Publishing Group.

Dilution: evidence

So much for the theory - what

about the evidence for dilution?

Figure 6.2 provides an example

where predator attack rate does

not vary with prey group size, so

here grouping by the prey results

in perfect dilution. In a group of

100, an individual suffers

1/100th the attack rate

compared to being alone. More

often, however, predator attack

rate will increase with group size because larger groups are more conspicuous.

Nevertheless, grouping usually still brings a net dilution advantage. For example, in

the Camargue marshes of the South of France, wild horses are attacked by blood

sucking flies (Tabanidae), which not only remove blood but also transmit bacterial

and viral diseases. During the weeks when these flies are most active, the horses

aggregate into larger groups. Duncan and Vigne (1979) varied group size

experimentally and found that more flies were attracted to larger groups of horses;

nevertheless, attack rate per horse was still lower in a larger group (Table 6.2).

A spectacular example of dilution is the winter aggregations of monarch butterflies

in Mexico, where thousands or millions of individuals assemble in enormous communal

roosts, clothing the trees over an area of up to 3 ha. The monarch is not a very palatable

butterfly but some birds attack them in these roosts. Counts of the remains of depredated

butterflies showed that although larger colonies attracted more predators, predation

rate per individual was lower in a larger colony, so the advantage of dilution outweighed

the disadvantage of greater conspicuousness in a larger roost (Calvert

et al

., 1979).

Grouping can

dilute an

individual prey's

risk of being

attacked

… even when

attack rate per

group increases

with group size