Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

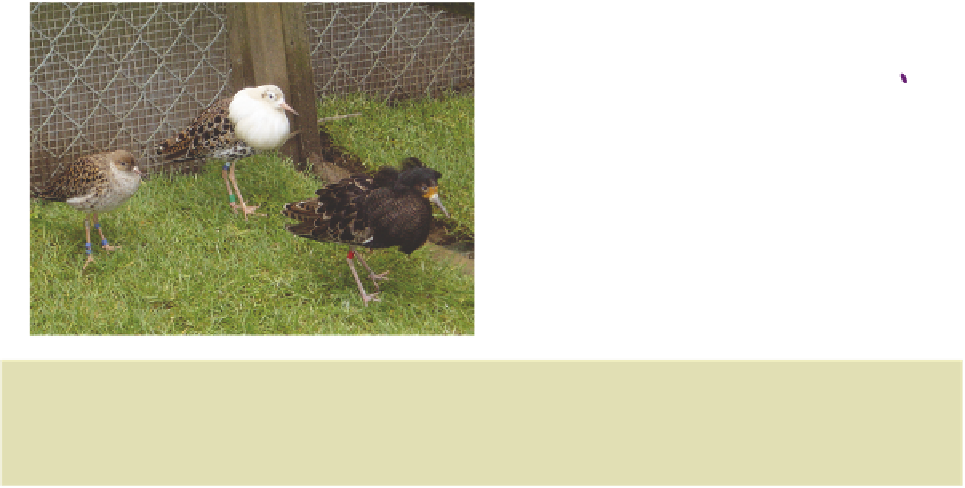

(a)

(b)

a.

b.

c.

4 mm

Fig. 5.18

Alternative genetic mating strategies. (a) In the ruff there are three male strategies: territorial

males (right) have dark ruffs, satellite males (centre) have white ruffs and female mimics (left) have no ruffs.

Photo © Susan McRae. (b) In the marine isopod

Paracerceis sculpta

there are three male morphs which differ

in size and behaviour; from left to right: alpha, beta and gamma males. From Shuster (1989).

The most likely way for this to come about is by frequency dependent selection. Let us

return to Fig. 5.9b, where producers and scroungers could coexist at a stable frequency.

In the spice finches the equilibrium was achieved by behavioural decision making. In an

evolutionary game involving genetic alternatives the equilibrium would come about by

natural selection. Imagine, for example, that the proportion of the genetic alternative

'scrounger' was below x in Fig. 5.9b. The scrounger morph has higher fitness than the

producer morph, so it will be favoured by selection and will increase in frequency across

the generations. As it does so, the pay-off for scrounging will decrease (more and more

competition between scroungers for resources produced by producers). On the other

hand, beyond x producers do better so they now increase in frequency (and so the

proportion of scroungers decreases). At x, there is a stable mixture of the two genetic

morphs because here each has the same reproductive success.

In theory, we might expect this kind of genetic polymorphism to be rare in nature

because conditional strategies with alternative tactics would enable competitors to fine

tune their behaviour to fit local environmental conditions and so would be favoured by

selection. Nevertheless, there are some marvellous cases of alternative genetic strategies;

some examples are now discussed.

Frequency

dependent

selection can lead

to equal success

for alternative

strategies

Ruffs: fighters, satellites and female mimics

The ruff is a shorebird with a remarkable difference between males and females (Fig. 5.18a).

Males are much larger and in the spring they develop ornamental neck ruffs and head tufts

and aggregate on display grounds (leks - see Chapter 10) to compete for females. The

scientific name

Philomachus pugnax

signifies 'love of fighting' and it describes well the

behaviour of the majority of the males; they have dark ruffs and tufts and they fight to