Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

depending on their direct assessment of female arrival rate, or

indirect assessment based on pat age and competitor numbers.

Competition by resource

defence: the despotic

distribution

Rich habitat

Consider the same situation as before: two habitats, one rich

and one poor. This time, though, the first competitors to settle

in the rich habitat defend resources by establishing territories

(pieces of ground containing the resource), so later arrivals

are forced to occupy the poor habitat even though they do less

well there than the individuals in the rich area. When the poor

habitat fills up with territory-defending individuals the latest

arrivals of all may end up being excluded from the resource

altogether (Fig. 5.4). This kind of situation is very common in

nature. In Wytham Woods, near Oxford, UK, the best breeding

habitat for great tits is in oak woodland. This is quickly

occupied in the spring and becomes completely filled with

territories. Some individuals are excluded from the oak wood

and have to occupy the hedgerows nearby where there is less

food and, consequently, lower breeding success. If great tits are

removed from the best habitat then birds rapidly move in from

the hedgerows to fill the vacancies (Krebs, 1971). Similarly, in

red grouse (

Lagopus lagopus scoticus

) territorial birds defend the richest areas of the heather

moors as breeding and feeding territories. Excluded birds have to go about in flocks and

exploit poor habitats where their chances of survival are low. Once again, if a territory

owner is removed its place is quickly taken by a bird from the flock (Watson, 1967).

In these examples the strongest individuals are despots, grabbing the best quality

resources and forcing others into low quality areas or excluding them from the resource

altogether.

Poor habitat

a

b

Number of competitors

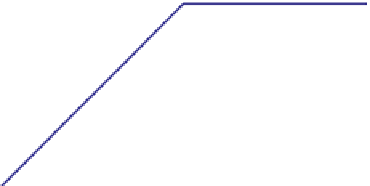

Fig. 5.4

Resource defence. Competitors

occupy the rich habitat first of all. At point

a this becomes full and newcomers are now

forced to occupy the poor habitat. When

this is also full (point b), further competitors

are excluded from the resource altogether

and become 'floaters'. After Brown (1969).

Removal

experiments show

that territorial

behaviour may

exclude some

competitors from

good habitats

The ideal free distribution with

unequal competitors

Most examples in nature will have features of both the simple models we have discussed

above. Perhaps the commonest situation will be where the best place to search depends

on where all the other competitors are, but within a habitat some individuals get more

of the resource than others. In the duck experiment, for example, population counts

showed a stable distribution of individuals but some ducks were better competitors than

others and grabbed most of the food (Harper, 1982). The stable distribution could come

about because of the way the subordinates distribute themselves in relation to the

despots. In effect, the despots are part of the habitat to which the subordinates respond

when deciding where to search.