Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

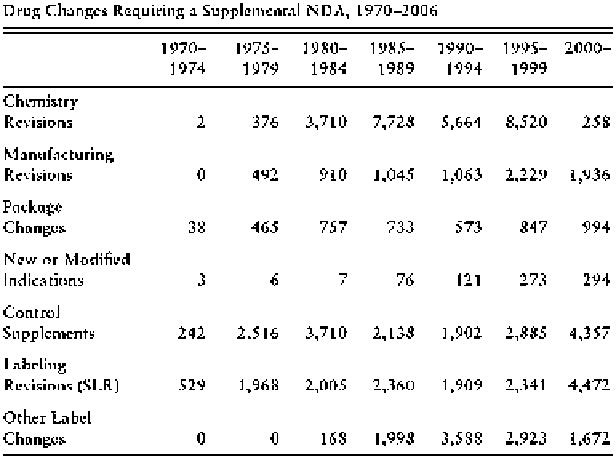

Fig. 11.1 Drug changes requiring a supplemental new drug application, 1970-2006 (Carpenter

2010

, p. 613)

limitations of causal inference in RCTs: the two phase III RCTs that granted the

approval of the drug do not usually capture the full range of effects of a drug.

However, it is useful to compare these figures with drug withdrawals. We should

always bear in mind that phase III trials are testing the safety and efficacy of a

compound, but not their full range of effects, which are only seen in phase IV. The

figures should be taken again with caution, since, as Carpenter (

2010

, ch. 9) warns,

the negotiation of each withdrawal depends on a number of circumstances outside

and inside the agency, among which a prominent one is the time constraints for the

review process (cf. Carpenter

2010

). However, very few compounds have been

withdrawn from the market in the United States during the last five decades for lack

of safety or efficacy after receiving the authorisation of the FDA: if we exclude the

drugs approved just before the new legal deadline established in 1992, for which

security issues seem to be more prominent, between 1993 and 2004 only 4 out of the

211 authorised drugs were withdrawn.

If we thus take label revisions and market withdrawals as rough indexes of the

external validity of the regulatory trials approved by the FDA, we may conclude

that the procedure is not foolproof (in the sense of anticipating every safety threat a

drug may pose), but that it does not fare completely badly either. Its main effects are

reasonably well anticipated. Of course, this is a black box argument: we know that

the four-phase regulatory system at the FDA screens off dangerous compounds, but

perhaps this is just because the pharmaceutical industry does not dare to submit any

potentially dangerous new compound. Assuming that the FDA system works (and

very few people question that it does), RCTs certainly do not explain its success

Search WWH ::

Custom Search