Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

the funicular railway up to

the ancient fortified village of

Montecatini Alto. In the quiet

main piazza, there are antique

shops and well-regarded res-

taurants with outdoor tables.

From the Rocca (castle) you

can take in sweeping views

over the mountainous

countryside.

Nearby at Ponte Buggia-

nese, in

San Michele

church,

you can see modern frescoes

by the Florentine artist Pietro

Annigoni (1910-88) on the

theme of Christ's Passion.

At Monsummano Terme,

another of Tuscany's well

known spa towns, the

Grotta

Giusti

spa prescribes the

inhalation of vapours from

hot sulphurous springs found

in the nearby caves.

Above Monsummano

Terme is the fortified

hilltop village of Monsum-

mano Alto, with its ruined

castle. Today, few people live

in the sleepy village, with its

pretty 12th-century church

and crumbling houses, but

there are some fine views

from here.

R

San Michele

Ponte Buggianese.

#

by appointment.

P

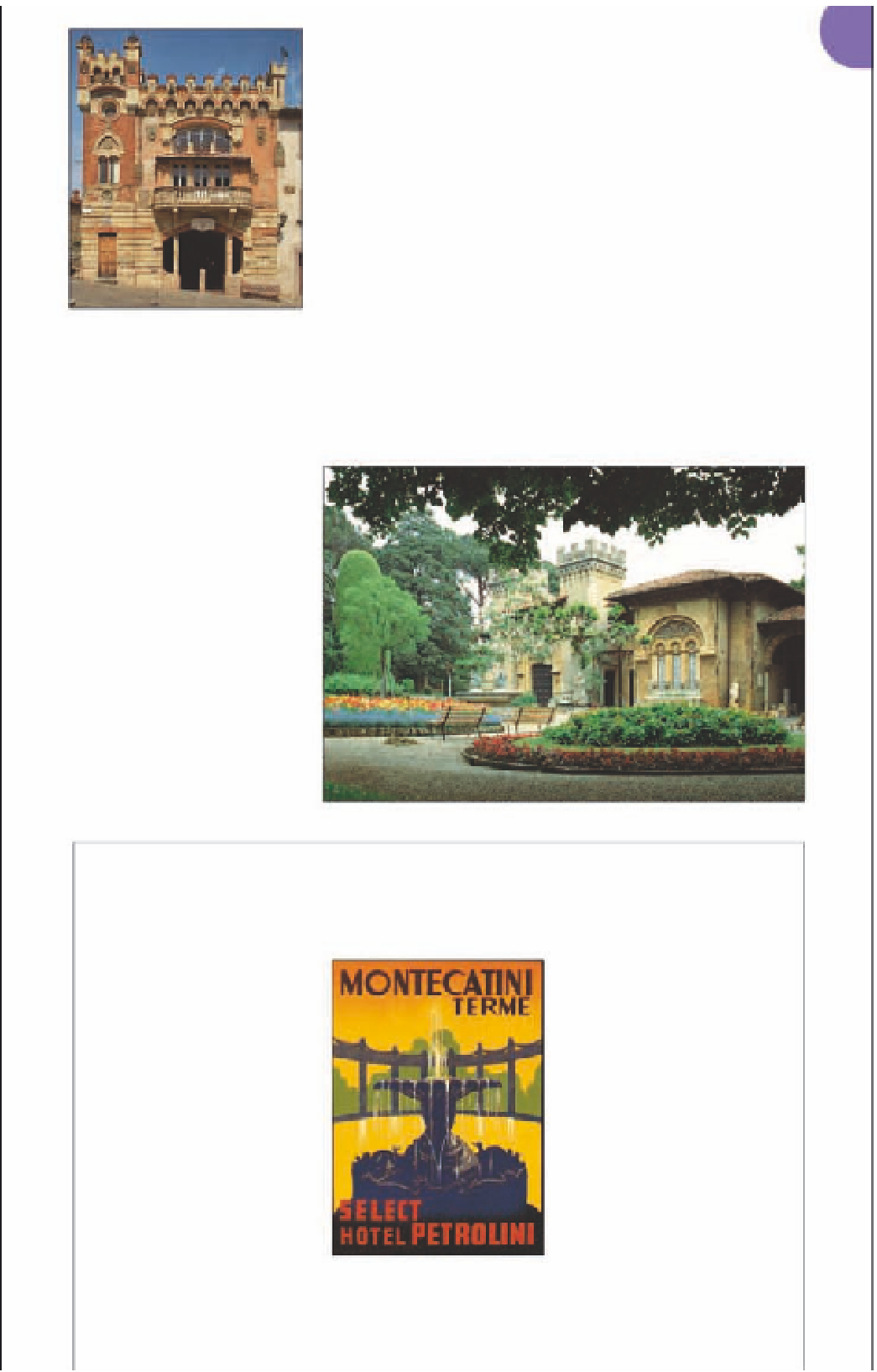

Theatre building in Montecatini

Alto's main square

Grotta Giusti

Monsummano Terme.

Tel

0572 907 71.

#

encouraged the development

of Montecatini Terme in the

18th century.

The most splendid is the

Neo-Classical Terme Tettuccio

(1925-8) with its circular,

marble-lined pools, fountains

and Art Nouveau tiles depic-

ting languorous nymphs.

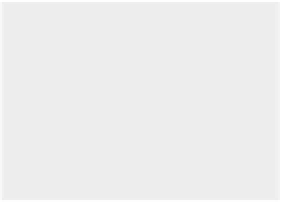

Terme Torretta, named after

its mock medieval tower, is

noted for its tea-time concerts,

while Terme Tamerici has

beautifully tended gardens.

Visitors can obtain day

tickets to the spas to drink

the waters and relax in the

reading, writing and music

rooms. More information is

available from the Direzione

delle Terme at Viale Verdi 41.

A popular excursion from

Montecatini Terme is to take

www

.grottagiustispa.com

9am-7pm daily.

&

The Terme Tamerici, built in Neo-Gothic style in the early 20th century

TAKING THE WATERS IN TUSCANY

The therapeutic value of bathing was first

recognized by the ancient Romans. They

were also the first to exploit the hot springs

of volcanic origin that they

found all over Tuscany. Here

they built bath complexes

where the army veterans who

settled in towns such as

Florence and Siena could

relax. Some of these spas, as

at Saturnia

(see p238)

, are still

called by their original

Roman names.

Other spas came into promi-

nence during the Middle Ages

and Renaissance: St Catherine

of Siena (1347-80)

(see p219)

,

who suffered from scrofula, a

form of tuberculosis, and

Lorenzo de' Medici (1449-92),

who was arthritic, both bathed in the

sulphurous hot springs at Bagno Vignoni

(see

p226)

to relieve their ailments. Tuscan spas

really came into their own in the early 19th

century when Bagni di Lucca was one of the

most fashionable spa centres in Europe,

frequented by emperors, kings and

aristocrats

(see p174)

.

However, spa culture in the

19th century had more to do

with social life: flirtation and

gambling took precedence

over health cures.

Today treatments such as

inhaling sulphur-laden steam,

drinking the mineral-rich

waters, hydro massage,

bathing and application of

mud packs are prescribed for

disorders ranging from liver

complaints to skin conditions

and asthma. Many visitors still

continue the tradition of

coming to fashionable spas

such as Montecatini Terme or

Monsummano Terme, not just for the bene-

fits of therapeutic treatment but also for

relaxation and in search of companionship.

1920s spa poster