Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

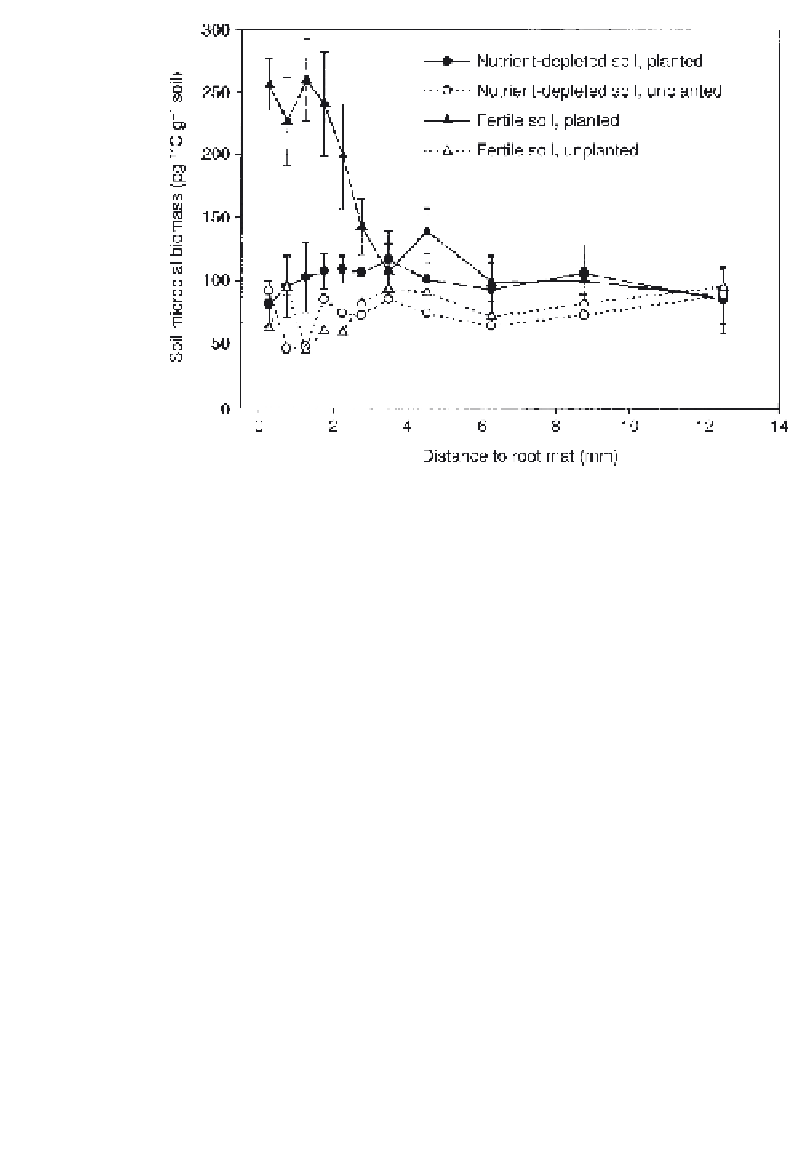

Fig. 5.5.2.

Soil microbial biomass

14

C at increasing distance from the root mat. Bars indicate

SE

(n= 4).

from labelled SOM was suppressed in the presence of living roots (e.g.

Jenkinson, 1977; Sparling

et al

., 1982; Martin, 1987), while others (Helal

and Sauerbeck, 1986; Sallih and Bottner, 1988; Cheng and Coleman,

1990) found a stimulatory effect. In this experiment, the increase in SMB

14

C in the rhizosphere of the

fertile

soil clearly showed that carbon was

moved from a pool that was not extractable after fumigation, to one that

was. Two possible explanations exist: (i)

14

C-labelled SOM was taken up

by the SMB, and hence decomposed (a priming effect); or (ii)

14

C-labelled

microorganisms in a dormant state were revitalized by the exudates, and

became prone to fumigation. The total changes in soil

14

C were not

significant in this short experiment and it is uncertain whether the roots in

the long term would have exerted a priming effect on the SOM. Different

changes in soil biological and physical factors induced by roots, depending

on experimental set up, may explain the conflicting results in the literature

(Cheng and Coleman, 1990; Dormaar, 1990). The complexity of the

situation is accentuated by the fact that no significant priming effect was

found in the

nutrient-depleted

soil. We propose three explanations: (i) the

SMB was nutrient limited which hampered decomposition of the labelled

SOM; (ii) the SMB in the

nutrient-depleted

soil was not capable of

decomposing the

14

C bound in microbial residues; and (iii) unlike in the

fer-

tile

soil, dormant SMB in the

nutrient-depleted

soil was not brought back into

an active state. The first explanation appears unlikely since microbial resi-

dues

would

contain

the

necessary

nutrients

for

microbial

growth.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search