Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

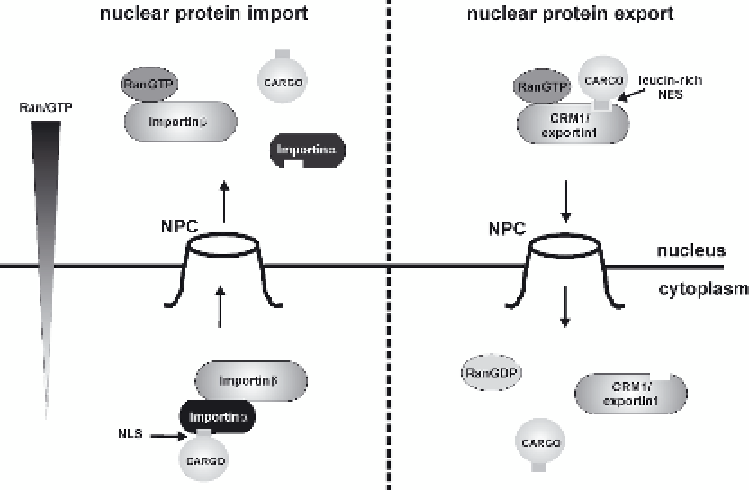

Fig. 1

Classical cellular pathways of nuclear protein import and export. Nuclear protein import:

in the cytoplasm, cargo, containing a nuclear localization signal (

NLS

), is bound by the het-

erodimeric import receptor, importin-α/importin-β; importin-α directly binds to the NLS-containing

cargo and importin-β mediates interactions with the nuclear pore complex (

NPC

) during translo-

cation. Within the nucleus, RanGTP binding causes a conformational change of importin-β, result-

ing in the release of the cargo. Nuclear protein export: in the nucleus, cargo, containing a

leucine-rich nuclear export signal (

NES

), interacts with the RanGTP complexed export factor

CRM1/exportin1, which directly interacts with components of the NPC. Hydrolysis of RanGTP

to RanGDP in the cytoplasm induces the release of the cargo. A gradient of RanGTP across the

nuclear envelope, resulting from the activity of the chromatin-associated nucleotide exchange fac-

tor RCC1 and the cytoplasmic GTPase-activating protein RanGAP, is considered the major driving

force for nuclear protein transport in both directions

Although the classical nuclear import pathway using importin-α as an adaptor

is believed to account for the majority of nuclear protein import, several alterna-

tive pathways exist. For instance, hnRNPA1 contains a different type of NLS

that is rich in aromatic residues and glycine (called M9 sequence), which binds

directly to the β-karyopherin transportin1, resulting in docking of the complex

at the NPC (Pollard et al. 1996). Also, several viral (e.g., Rex of HTLV-1and Rev

of HIV-1) and cellular proteins (e.g., c-fos) are able to bind directly to various

members of the importin-β family (importin-β, transportin, importin5, impor-

tin7) via arginine-rich sequences without the need for an additional adapter pro-

tein (Palmeri and Malim 1999; Henderson and Percipalle 1997; Arnold et al.

2006a, 2006b).

Interestingly, the M9 sequence not only acts as an NLS but also mediates

nuclear export, thus constituting a bidirectional signal for nucleocytoplasmic shut-

tling (Michael et al. 1995). Nuclear export of proteins, however, is in most cases