Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

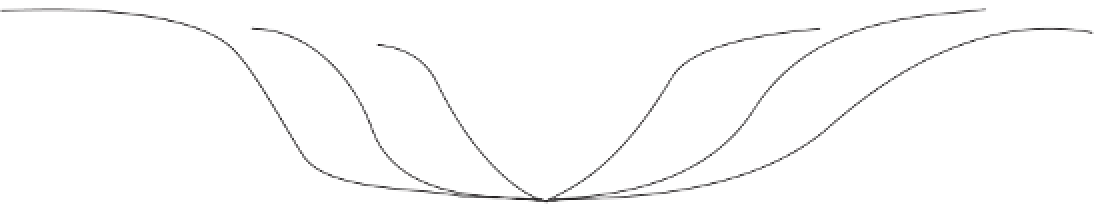

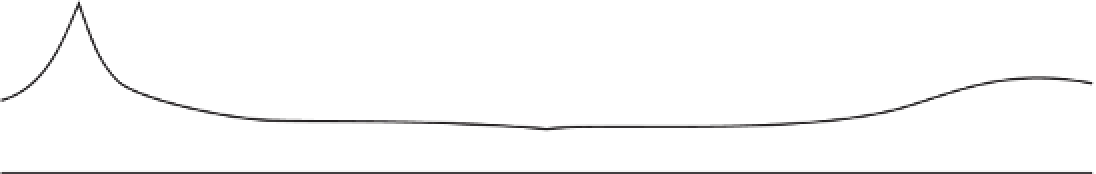

According to Penck's arguments, slopes may either

recede at the original gradient or else flatten, accord-

ing to circumstances. Many textbooks claim that Penck

advocated 'parallel retreat of slopes', but this is a false

belief (see Simons 1962). Penck (1953, 135-6) argued

that a steep rock face would move upslope, maintain-

ing its original gradient, but would soon be eliminated

by a growing basal slope. If the cliff face was the scarp

of a tableland, however, it would take a long time to

disappear. He reasoned that a lower-angle slope, which

starts growing from the bottom of the basal slope, replaces

the basal slope. Continued slope replacement then leads

to a flattening of slopes, with steeper sections formed

during earlier stages of development sometimes surviv-

ing in summit areas (Penck 1953, 136-41). In short,

Penck's complicated analysis predicted both

slope reces-

sion

and

slope decline

, a result that extends Davis's

simple idea of

slope decline

(Figure 1.3). Field stud-

ies have confirmed that slope retreat is common in a

wide range of situations. However, a slope that is actively

eroded at its base (by a river or by the sea) may decline if

the basal erosion should stop. Moreover, a tableland scarp

retains its angle through parallel retreat until the erosion

removes the protective cap rock, when slope decline sets

in (Ollier and Tuddenham 1962).

Eduard Brückner

and

Albrecht Penck

's (Walther's

father) work on glacial effects on the Bavarian Alps and

their forelands provided the first insights into the effects

of the Pleistocene ice ages on relief (Penck and Brückner

1901-9). Their classic river-terrace sequence gave names

to the main glacial stages - Donau, Gunz, Mindel, Riss,

and Würm - and sired Quaternary geomorphology.

Modern historical geomorphology

Historical geomorphology has developed since Davis's

time, and the interpretation of long-term changes of

landscape no longer relies on the straitjacket of the geo-

graphical cycle. It relies now on various chronological

analyses, particularly those based on stratigraphical stud-

ies of Quaternary sediments, and upon a much fuller

appreciation of geomorphic and tectonic processes (e.g.

Brown 1980). Observed stratigraphical relationships fur-

nish relative chronologies, whilst absolute chronologies

derive from sequences dated using historical records,

radiocarbon analysis, dendrochronology, luminescence,

palaeomagnetism, and so forth (p. 354). Such quantita-

tive chronologies offer a means for calculating long-term

rates of change in the landscape.

It is perhaps easiest to explain modern historical geo-

morphology by way of an example. Take the case of

the river alluvium and colluvium that fills many valleys

in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Claudio

Vita-Finzi (1969) pioneered research into the origin

of the valley fills, concluding that almost all alluvium

Eduard Brückner and Albrecht Penck

Other early historical geomorphologists used geologi-

cally young sediments to interpret Pleistocene events.

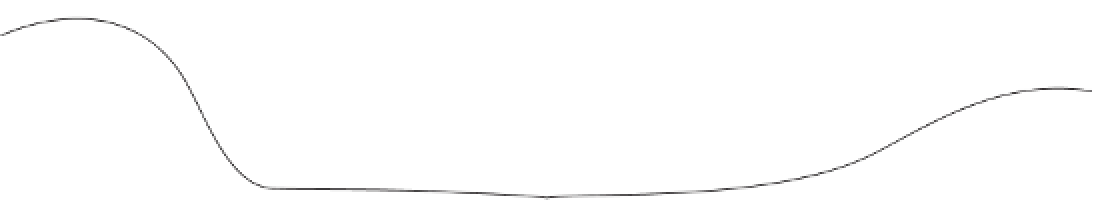

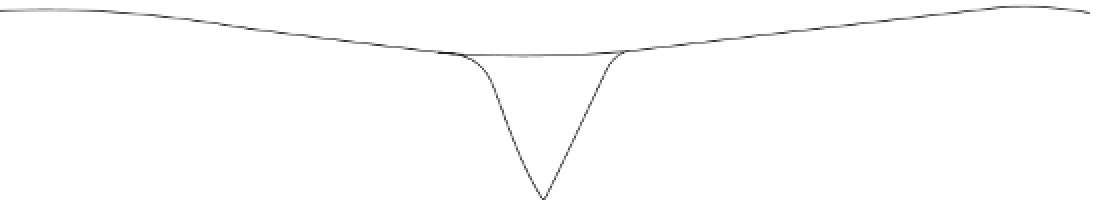

Slope recession or backwearing

(Penck)

Slope decline or downwearing

(Davis)

Time

6

5

4

3

2

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

Pediplain

Peneplain

Figure 1.3

Slope recession, which produces a pediplain (p. 381) and slope decline, which produces a peneplain.

Source:

Adapted from Gossman (1970)