Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

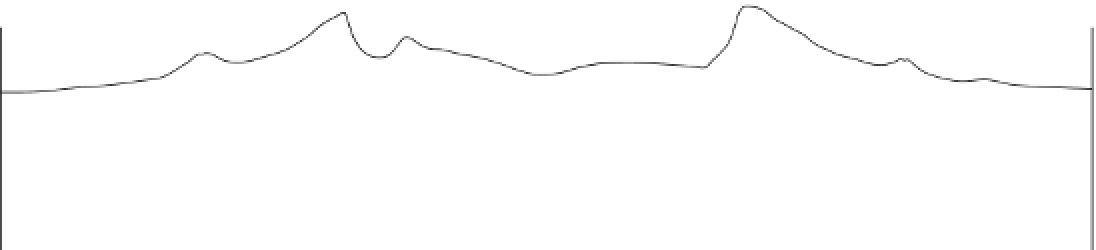

Caldera

Volcano (Wizard Island)

Figure 5.8

Crater Lake caldera, Oregon, USA.

Source:

Adapted from MacDonald (1972, 301)

calderas between 22 million and 30 million years old.

Ignimbrites from these calderas cover 25,000 km

2

.

down established valleys. Erosion then reduces the adja-

cent hillside leaving the more resistant volcanic rock as a

ridge between two valleys. Such inverted relief is remark-

ably common (Pain and Ollier 1995). On Eigg, a small

Hebridean island in Scotland, a Tertiary rhyolite lava

flow originally filled a river valley eroded into older basalt

lavas. The rhyolite is now preserved on the Scuir of Eigg,

an imposing 400-m-high and 5-km-long ridge standing

well above the existing valleys.

Indirect effects of volcanoes

Volcanoes have several indirect impacts on landforms.

Two important effects are

drainage modification

and

relief inversion

.

Radial drainage patterns often develop on volca-

noes, and the pattern may last well after the volcano

has been eroded. In addition, volcanoes bury pre-

existing landscapes under lava and, in doing so, may

radically alter the drainage patterns. A good example

is the diversion of the drainage in the central African

rift valley (Figure 5.10). Five million years ago, volca-

noes associated with the construction of the Virunga

Mountains impounded Lake Kivu. Formerly, drainage

was northward to join the Nile by way of Lake Albert

(Figure 5.10a). When stopped from flowing north-

wards by the Virunga Mountains, the waters eventually

overflowed Lake Kivu and spilled southwards at the

southern end of the rift through the Ruzizi River into

Lake Tanganyika (Figure 5.10b). From Lake Tanganyika,

the waters reached the River Congo through the River

Lukuga, and so were diverted from the Mediterranean

via the Nile to the Atlantic via the Congo (King 1942,

153-4).

Occasionally, lava flows set in train a sequence of events

that ultimately inverts the relief - valleys become hills

and hills become valleys (cf. p. 156). Lava tends to flow

IMPACT CRATERS

The remains of craters formed by the impact of asteroids,

meteoroids, and comets scar the Earth's surface. Over

170 craters and geological structures discovered so far

show strong signs of an impact origin (see Huggett 2006).

Admittedly, impact craters are relatively rare landforms,

but they are of interest.

In terms of morphology, terrestrial impact structures

are either simple or complex (Figure 5.11). Simple

structures, such as Brent crater in Ontario, Canada, are

bowl-shaped (Figure 5.11a). The rim area is uplifted and,

in the most recent cases, is surmounted by an overturned

flap of near-surface target rocks with inverted stratigra-

phy. Fallout ejecta commonly lie on the overturned flap.

Autochthonous target rock that is fractured and brec-

ciated marks the base of a simple crater. A lens of shocked

and unshocked allochthonous target rock partially fills

the true crater. Craters with diameters larger than about