Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

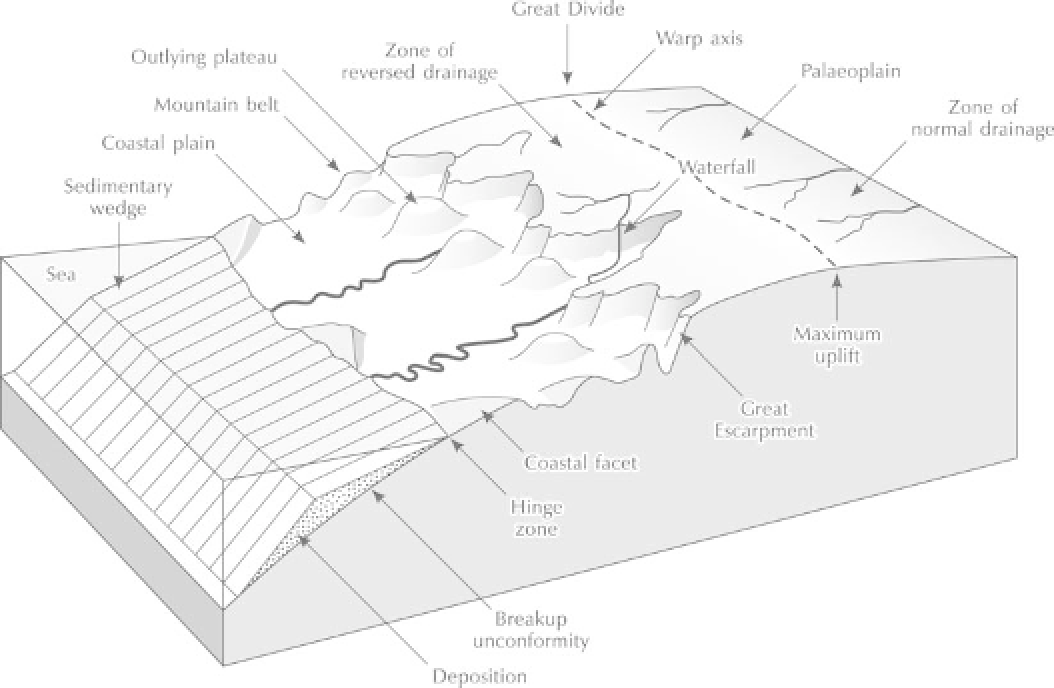

Figure 4.7

The chief morphotectonic features of a passive continent margin with mountains.

Source:

Adapted from Ollier and Pain (1997)

where the valleys deeply incised into the escarpment,

although modified by glaciers, are still recognizable

(Lidmar-Bergström

et al

. 2000). Some passive margins

that lack great escarpments do possess low marginal

upwarps flanked by a significant break of slope. The

Fall

Line

on the eastern seaboard of North America marks

an increase in stream gradient and in places forms a

distinct escarpment. Below great escarpments,

rugged

mountainous areas

form through the deep dissection of

old plateaux surfaces. Many of the world's large water-

falls lie where a river crosses a great escarpment, as in

the Wollomombi Falls, Australia.

Lowland

or

coastal

plains

lie seawards of great escarpments. They are largely

the products of erosion. Offshore from the coastal plain

is a wedge of sediments, at the base of which is an

unconformity, sloping seawards.

Interesting questions about passive-margin land-

forms are starting to be answered. The Western Ghats,

which fringe the west coast of peninsular India, are a great

escarpment bordering the Deccan Plateau. The ridge

crests stand 500-1,900 m tall and display a remarkable

continuity for 1,500 km, despite structural variations.

The continuity suggests a single, post-Cretaceous pro-

cess of scarp recession and shoulder uplift (Gunnell

and Fleitout 2000). A possible explanation involves

denudation and backwearing of the margin, which pro-

motes flexural upwarp and shoulder uplift (Figure 4.9).

Shoulder uplift could also be effected by tectonic pro-

cesses driven by forces inside the Earth.

Active-margin landforms

Where tectonic plates converge or slide past each other,

the continental margins are said to be

active

. They may

be called

Pacific-type margins

as they are common

around the Pacific Ocean's rim.