Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

predation in the micro-foodweb is just one process in the overall functioning of the

rhizosphere which is broadly based on mutualism (see Section IV.3.2). As explained in

Chapter III.4‚ it is possible to identify three successive levels of interactions between

micro-organisms and invertebrates‚ based on the size of the latter organisms.

Among the larger invertebrates‚ interactions with the microflora shift from predation

to external and internal mutualisms‚ while the invertebrates increasingly affect the struc-

ture of the liner and soil system. Micro-foodwebs adapt to the soil structure and their

development and activity is largely dependent on the nature and size of the system of soil

pores and the proportion of these that are filled with water. Litter-transformers are unable

to dig the soil or build nests and rely on the relatively-inefficient external rumen type

of digestion. Consequently‚ their activities are largely restricted to the litter system.

At the next larger size level‚ earthworms‚ termites and many ants have well developed

digging and tunnelling abilities and the capacity to create such diverse structures as

nests‚ galleries‚ burrows‚ surface sheathings and casts that greatly modify soil processes.

For this reason‚ they have been called 'ecosystem engineers' (Stork and Eggleton‚ 1992;

Jones

et al

.‚ 1997). The first two groups of these organisms have developed efficient

internal mutualistic digestion systems with the microflora and‚ where populous‚ they

play dominant roles in soil function (see Sections IV.4 and IV.5).

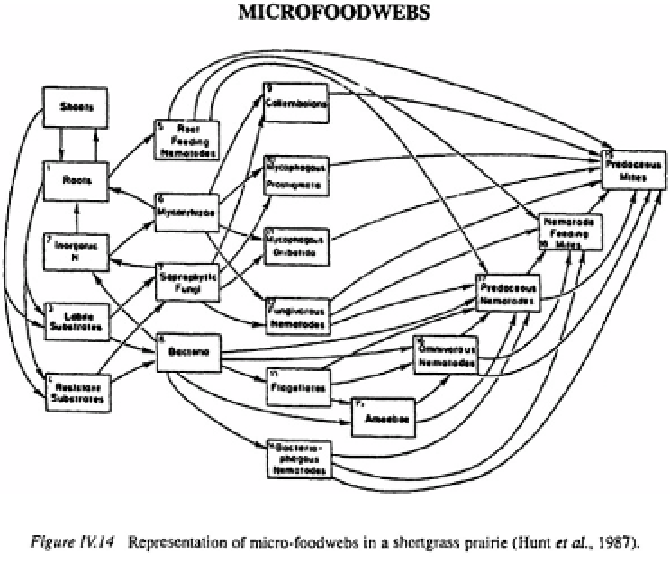

The composition of microfoodwebs

The soil micropredator foodwebs include micro-organisms‚ mainly bacteria and fungi‚

protists‚ nematodes - and some predaceous Acari (Figure IV.14). Several levels of com-

plexity exist since the system includes microbial grazers‚ predators and superpredators.