Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

22 % of total carbon and 22 to 72 % of the nitrogen of freshly-dead leaves (Toutain‚

1987a; François

et al.‚

1986) and they may comprise 25 % of the weight of Beech

(

Fagus sylvatica

) leaves (François

et al.‚

1986).

Phenol-protein complexes are also an important component of decomposing roots;

in Beech

(Fagus sylvatica)

roots‚ they make up 15 % of the overall weight‚ 17 % of

the total carbon and 85 % of the total nitrogen (Baraer and Toutain‚ 1987). However‚ due

to the large variety of tannins and cytoplasmic proteins‚ it is probable that a wide range

of phenol-protein associations exist‚ all with potentially-different degrees of resistance

to decomposition (Waterman and McKey‚ 1989).

Concentrations of condensed tannins and phenols varied respectively‚ in the ranges

1.08-9.60 % and 3.64-10.10 % of the dry weight of mature leaves over 10 forest sites

distributed throughout the tropics (Waterman and McKey‚ 1989). There is some evidence

to suggest that where these products occur at high concentrations in leaves‚ they may

act as an antiherbivore defence. In soils of poor nutrient status‚ plants grow slowly

and may allocate more carbon to the production of secondary compounds (Baas‚ 1989)

since this is less limiting than nutrients‚

The degradation of phenol-protein complexes is usually extremely slow‚ unless

particular organisms capable of decomposing them are present‚ namely‚ certain earth-

worms‚ termites and 'white-rot' basidiomycote fungi (Figure IV.8b and c). In the absence

of such organisms‚ degradation of these brown pigments occurs through progressive

hydrolysis caused by percolating water (the so-called'infusion'effect) (Toutain‚ 1987a).

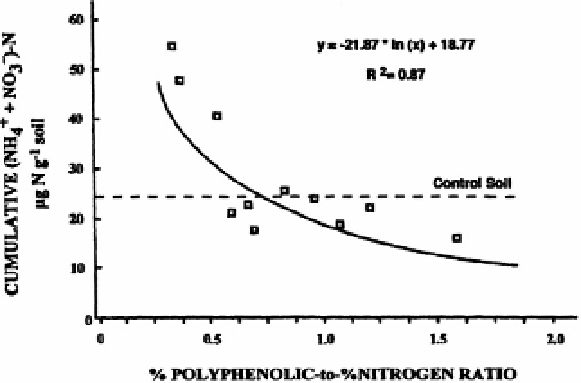

In a litter-bag experiment at Yurimaguas‚ in Peruvian Amazonia‚ Palm and Sánchez

(1990) found a negative relationship between the ratio of polyphenolic to nitrogen

contents and the release of mineral nitrogen from decomposing legume leaf litter

(Figure IV.9).