Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

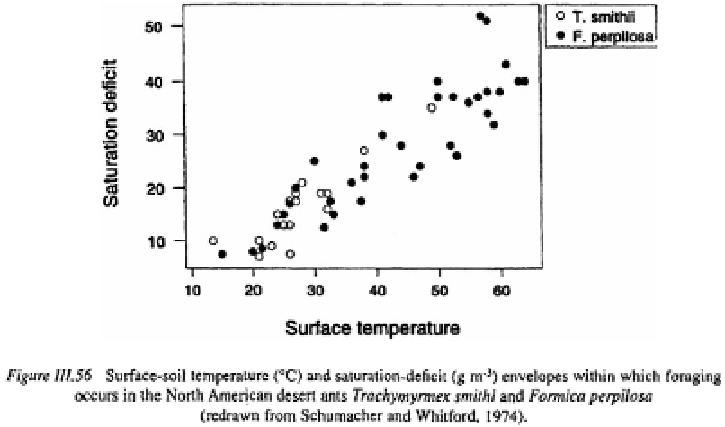

where the rate at which workers returned to a nest of the North American desert fungus

feeding ant,

Trachymyrmex smithi

declined to zero at saturation deficits of greater than

and at soil surface temperatures greater than 50°C. In contrast, workers of

Formica

perpilosa

at the same site continued to forage at temperatures of 55 °C and saturation

deficits of because they were able to replace lost fluid from the honey dew that

they feed on and because of their greater tolerance of water loss (Schumacher and

Whitford, 1974).

Activities are also constrained by strong diurnal rhythms (Hunt, 1974; Roces and

Nunez, 1989) and daily cycles of foraging activity may be modified to avoid predation

and reduce competition (Hölldobler and Wilson, 1990). At a seasonal scale, foraging

may be constrained by environmental conditions. In a Nearctic temperate environment,

the three seed-harvesting species of

Pogonomyrmex

studied by McKay (1981) foraged

most actively during the warmer summer months but were inactive during the winter.

Plant materials

Tobin (1994) argued that while the ants as a group have not specialised in the digestion

of cellulose, their abundance and dominance in many environments is due to their

capacity to exploit plant resources. Many species ingest a wide variety of plant materials,

both vegetative and reproductive, in appreciable and perhaps hitherto unrecognised

quantities (Tobin, 1994). In particular, many ants feed on seeds, seed-associated struc-

tures, plant secretions and other products or little-modified plant materials excreted by

herbivores.

Few ants feed exclusively on plant materials although many use them on a seasonal

or facultative basis. For example, the granivorous ant

Messor pergandei

may consume

leaves, stems and flower parts when seed sources are in short supply (Rissing and

Wheeler, 1976). Vegetative tissues are less commonly eaten although those taken tend