Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

Markedly different patterns of abundance occur at decreasing spatial scales (see

reviews in Edwards and Bohlen, 1996; Lavelle, 1983c; Lee, 1985):

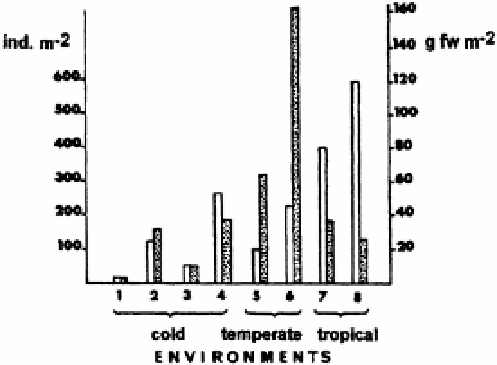

(i) at a worldwide geographical scale there is a clear thermo-latitudinal gradient, as mean

population density in natural environments tends to increase from a few tens on average

in cold temperate areas to maximum values of several hundred in the tropics. In contrast,

biomass increases from cold to mild temperate environments and then decreases again

towards tropical latitudes (Figure III.44);

(ii) at a regional (landscape) scale, soil and vegetation regimes greatly influence

earthworm abundance (Stöckli, 1928). Grasslands tend to have much larger populations

than forests. This is particularly in the case of temperate or tropical pastures colonised

either by exotic peregrine species, or by adapted local species. These may have biomasses

of 1 t or more whereas an adjacent forest may only have approximately half as much

(Lavelle and Pashanasi, 1989). Large biomasses may also be associated with a high soil

nutrient status as, for example, in tropical rainforest communities (Fragoso and Lavelle, 1992).

(iii) at a local scale, variation in soils, land-use and cultivation techniques greatly

influence earthworm populations. Cultivation and the application of nematicides and

fungicides generally depress earthworm abundances. In contrast, most herbicides have

no significantly deleterious effects and cattle grazing in pastures has positive effects

(Edwards and Lofty, 1982; Haines and Huren, 1990; House and Parmelee, 1985; Lavelle

and Pashanasi, 1989; Lee, 1985; McKay and Kladivko, 1985; Parmelee

et al.,

1990;

Yule

et al.,

1991).