Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

Spatial distribution

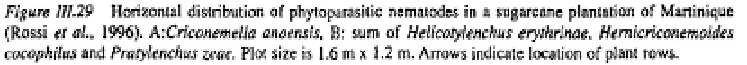

At a mesoscale level of approach, that of an experimental plot, the horizontal distribution

of nematode populations is very uneven. At sites in nine prairies in Iowa, Schmitt and

Norton (1972) found more heterogeneity within than between sites. In a soy-bean field

in Michigan, Robertson and Freckman (in Roberston, 1994) found nematodes to be

distributed in large patches

ca.

200 m in diameter with population density variations

spanning two orders of magnitude. In tundra soils, nematode communities reflect the

mosaic of microsites with densities a hundred times greater in grass stands than in bare

soil (Kuzmin, 1976). Similar differences have also been reported for soil within and

between rows in cultivated soils (Ferris and McHenry, 1976) and in a sugarcane field in

Martinique (Rossi

et al.,

1996, Figure III.29).

Such factors as total-C, assimilable P, pH, Ca, aeration and moisture may influence

the micro-distribution of nematodes (Yeates, 1981). Interactions with other organisms,

especially roots (which attract them) or earthworms (whose activities depress nematode

populations) also modify distribution patterns (Yeates, 1981). In consequence, the distri-

bution of phytoparasitic nematodes in cultivated fields largely reflects that of the plants

(Francl, 1986).

Vertical distribution

Nematode populations are generally concentrated in the upper 5 to 10 cm of soil

although they may also occur at depths of 50 cm and more (Sohlenius and Sandor, 1987).

Their distribution follows those of site organic resources and thus forest communities

have more superficial patterns of vertical distribution than grassland communities (see,

e.g.,

Yeates and Coleman, 1982; Hota

et al.,

1988). Vertical migration is limited, with

most movement being due to transport on growing root-tips (Yeates, 1981). Significant

differences exist between populations of different species and ecological categories