Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

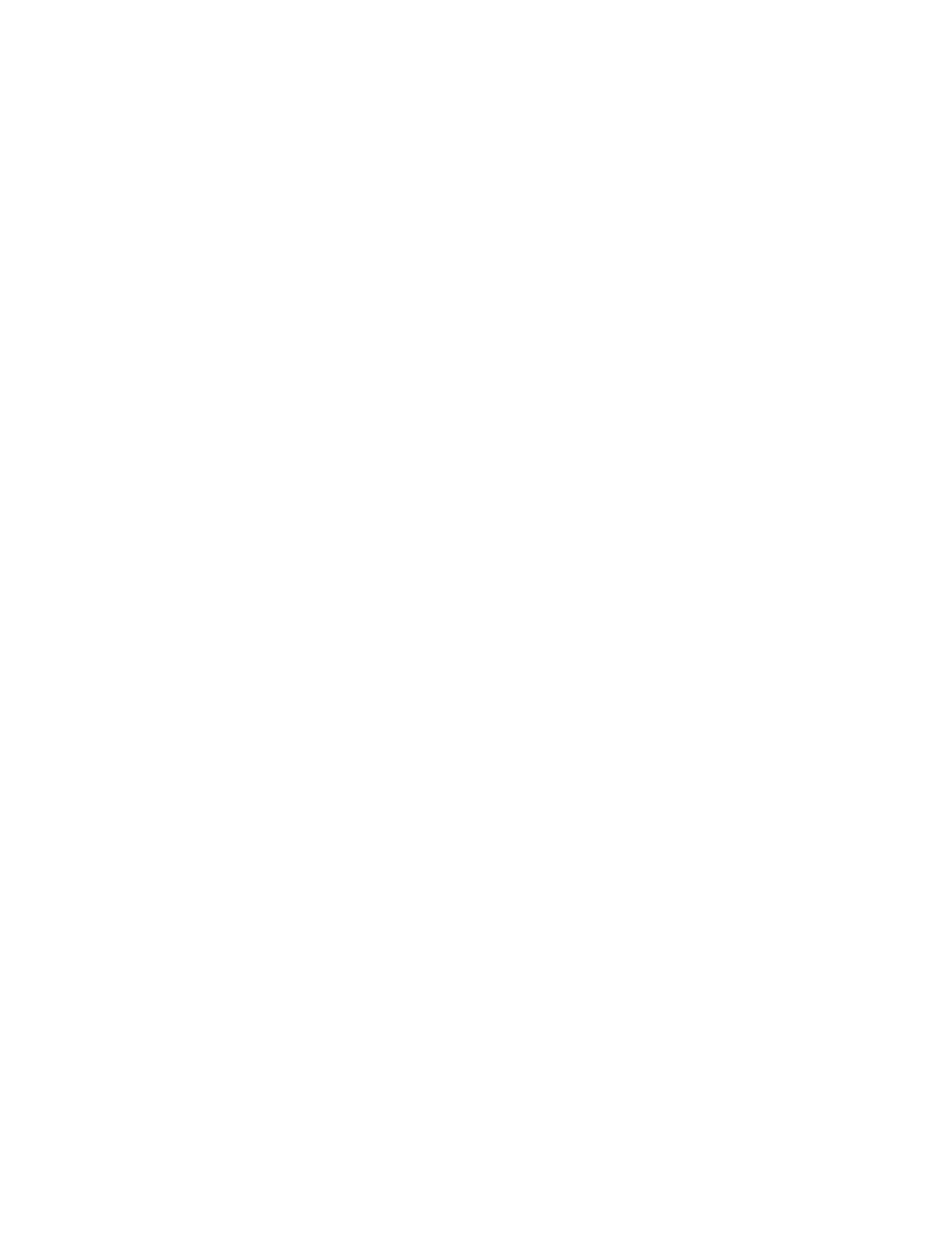

Table 3.1

Families of Reddish Prairie Soils in the Southern Great Plains Correlation Area

Degree of

Weathering

Size of

Solum

Family

Stage

Texture Class

Drainage

Craig

Maximal

Medium

Good

Strong

Medium

Dennis

Medial

Medium to

moderately fine

Good to moderately good

Strong

Medium

Hockley

Maximal

Moderately coarse

Good to moderately good

Strong

Medium

Kirkland

Medial

Moderately fine

Good to moderately good

Medium

Medium

La Bette

Medial

Loamy

Good

Medium

Medium

Pratt

Minimal

Coarse

Good

Weak

Medium

Teller

Minimal

Loamy

Good

Weak

Medium

Tishomingo

Medial

Moderately coarse

Good

Strong

Thin

Wilson

Maximal

Loamy

Moderately good

Strong

Medium

and describe the morphology and properties of soil proÝles. This lack of standards hampered

pedology and resulted in classiÝcation schemes shrouded with cloudy concepts that lacked opera-

tional deÝnitions.

As an example, the U.S. 1938 classiÝcation system (USDA, 1938) followed the concepts of

zonal and azonal soils, lacked operational deÝnitions, and consequently failed to meet all the needs

of the soil science community. In the 1938 system, one of the zonal soils, Reddish Prairie Soils,

is described as dark-brown or reddish-brown soil grading through reddish-brown heavier subsoil,

medium acid. This description is very vague, and without the knowledge that these soils occur in

the southern Great Plains of the United States, the soil scientist might believe that these soils are

in several parts of the world. Aside from the indistinct categories within the 1938 scheme, the

system did not offer a means to differentiate soils both among taxa and within the same taxa. For

example, Table 3.1 illustrates the families from a card dated November 26, 1951, used presumably

by the correlators and Ýeld soil scientists to differentiate among the Reddish Prairie Soils. Obvious

deÝciencies include a lack of deÝnitions for column headings such as stage, degree of weathering,

and size of solum. Additionally, there are no operational deÝnitions to differentiate any of the

classes within the columns. This means that the differences among the differentiae, such as the

degrees of weathering, are based on judgment and experience. The terms may have valid meaning

to the local soil scientists. Soil scientists from different parts of the world, however, converging on

the southern Great Plains, could engage in interesting discussions, but likely not reach agreement

on whether a given soil exhibits medium or strong weathering. Furthermore, the differentiae are

deÝned in neither the

(Soil Survey Staff, 1951) nor anywhere else.

The information in Table 3.1 is useful only to those who already have a familiarity with these

soils. The differentiae provide little value in distinguishing these soils, even for the most experienced

soil scientist.

Table 3.2 is also a card dated November 25, 1951, that attempts to provide facts about the Craig

soils. Again, the information is scant and provides little value for a soil scientist unfamiliar with

these soils or the area in general. Table 3.3 is a modern description of the same soil series.

Soil Survey Manual

MODERN SOIL CLASSIFICATION

After World War II, agriculture felt the effects of economic reconstruction and the expansion

of global markets, and there was a renewed interest in soil conservation and alternative land uses,

which helped invigorate soil survey activities. Soil scientists began identifying many new soils,

and classiÝcation systems needed to track all the newly recognized soils. The United States Soil

Conservation Service (now the Natural Resources Conservation Service), under the leadership of

Guy Smith, accepted the challenge and made giant strides in improving soil classiÝcation. Work

to develop a new U.S. soil classiÝcation system commenced in 1951.