Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

Outside the UK, there are many

potential sites for tidal stream

power - the Strait of Gibraltar,

the Bosphorus, the Cook Strait in

New Zealand, the Bass and Torres

Straits in Australia. But don't

count on seeing anything from the

Mediterranean, where the tide is

minimal.

Wave power

Wave power is harder to capture

than tidal power, because waves

are a more chaotic form of motion

than tides or currents. The up,

down and rocking motion of waves

is more difficult to transform into

the rotational motion required for

electricity generation.

However, this was achieved

in the early 1970s by Professor

Stephen Salter of Edinburgh

University, with a device that

was dubbed Salter's Duck. It was

essentially composed of float-

ing containers, tied together and

loosely tethered to the sea floor.

The waves rocked these containers,

which converted the rocking into a

rotational motion that could spin

a generator. Development of this

was dropped when public funding

was cut in the 1980s. But the idea

has lived on in the work of some of

Professor Salter's Edinburgh pupils

in a company called Pelamis Wave

Power. Pelamis (the name of a sea

snake) has installed several of its

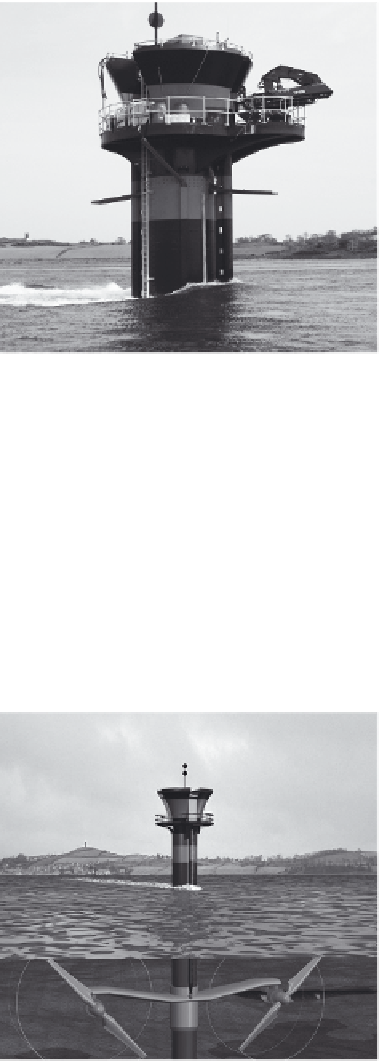

The Seagen tidal power turbine in Strangford

Lough, on Northern Ireland's north coast,

photographed above the water and depicted

below via an artist's impression demonstrating the

turbine's blades beneath.

Owned by Marine Current Turbines Ltd, Seagen

is the world's first large-scale commercial tidal

energy converter. Installed in April 2008, it was

connected to the national grid in July that year,

and generates 1.2 megawatts of electricity for

between 18 and 20 hours a day.

The turbines have a patented feature by which the

rotor blades can be pitched through 180 degrees.

This allows it to exploit water flowing in both

directions - as the tides come in and out of the

straits of the lough.