Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

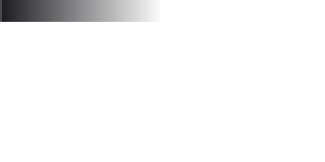

All comers,

stratified analysis

Phase III

1

Drug

development

Dx-gated

patient selection

Phase I

Phase IIa

Phase IIb

Phase III

2

3

All comers,

new Dx discovery

Phase III

Companion Dx

development

Exploratory

biomarker discovery

Diagnostic

partnering

Assay development,

technical validation

Clinical

verification

Clinical

qualification

0

Time (years)

1

2

3

4

5

Potential phase IIb outcomes:

1) Diagnostic enriches for clinical benefit but precise cutoff not identified

2) Diagnostic enriches for clinical benefit with clear cutoff

3) Diagnostic fails to enrich for clinical benefit

FIGURE 4.4

Hypothetical timelines for early clinical development of an asthma drug and a companion diag-

nostic (Dx). To prospectively validate a Dx test in a phase III pivotal trial, a candidate biomarker should be identi-

fied via exploratory studies while the drug candidate is in very early stages of clinical development. This early

activity will allow selection of a partner diagnostic company and development and technical validation of a proto-

type clinical assay in time to permit clinical verification that the biomarker enriches for clinical benefit in a phase

II proof-of-concept study without delaying the clinical development timeline. Because the companion Dx develop-

ment is done at risk, there are several potential implications for how the biomarker may be used in a pivotal trial;

three possibilities as discussed in the text are shown.

3.

If the diagnostic hypothesis fails to be validated in the proof-of-concept study but there

is evidence of clinical benefit in all comers regardless of baseline biomarker levels, an

unstratified Phase III trial may be pursued. The greater numbers enrolled and opportunities

for additional sample collection in Phase III may enable new exploratory efforts to

discover diagnostic biomarkers. However, even if these efforts are successful, a subsequent

additional pivotal trial may be necessary to prospectively validate the diagnostic.

In order to have data on the biomarker in time so as not to impede the clinical drug devel-

opment process, an early effort to get biomarker reagents in place is likely needed well before

the start of Phase II. Even if one expects to do a pre-specified retrospective analysis of Phase

II data, a commitment to the diagnostic development would need to occur in parallel with

the Phase II program in order to have everything ready to be run in 'real-time' to validate the

predictive effect in Phase III through prospective randomization using the commercially rep-

resentative assay on the intended platform. If the drug is a new entity with no prior clinical

data to mine, there is an even higher risk that one may need more than a single Phase II trial

to sufficiently mitigate a risk of the test not being able to reproducibly predict a treatment

benefit in the subsequent trials using the same pre-specified threshold for being 'diagnostic-

positive'. Biases abound in the clinical trial setting. In addition to the inherent variability

from trial to trial is the potential for other real differences in the biology between slightly

different populations, such as effects from studying patients of different ages and ethnicities,

with different degrees of disease severity, different co-morbid conditions, or different back-

ground medications.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search