Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

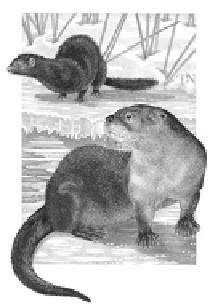

Although mink raised on fur farms come in various mutant designer shades, wild mink sport a rich,

brown pelage, except for a white chin patch. Their dense coat of underfur is covered by the long, dark

guard hairs which give them their sleek, glossy appearance. Despite the availability of ranch mink, wild

mink remain highly prized in the fur trade; evidently nature can still do a better job than humans of

equipping mink with a dense, glossy coat.

Like all of the mustelids, mink deposit scent from their anal glands. However, the mink's scent is

particularly strong and unpleasant; many would rate it worse than the odor of skunk, although the mink

can't spray its scent as a defensive measure.

Mink breed during a period of over two months, starting in February. Implantation of the fertilized

eggs is delayed for about a month; then a pregnancy of roughly twenty to forty days ensues. The

young—typically three or four—are born, blind and covered with fine hair, in a hollow log, an expro-

priated muskrat house, or a burrow or cave in the bank.

THE RIVER OTTER

If many members of the weasel clan are viewed by some with loathing and disdain, the river otter

(Lutra canadensis)

manages to salvage the family honor. Whether in the wild or in a zoo or animal

park, it seems that everyone loves otters! The reasons aren't difficult to ascertain. With its bewhiskered

visage, comically turned-down mouth, and often playful nature, the otter seems downright appealing to

humans.

Aside from these attractive qualities, the otter is worthy of attention because of the way in which it

has mastered its mostly watery habitat. Flawlessly equipped for this role, otters are a superb example

of evolutionary engineering. The mink functions quite well in and under the water, but the otter simply

revels in it.