Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

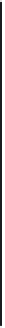

Table 6.3

Species-specific behaviour of chickens with regard to adequate housing systems (Fölsch

and Hörning 1996; Hörning 1998)

Functional unit

Species-speciic behaiours

Appropriate housing

Feeding

Scratching and pecking

Intake of plant material

Littered area for scratching,

feeding grains in the litter

Supply of roughage, access to

pasture

Locomotion

Walking, flying, fluttering

Enough space, elevated perches

Resting behaviour

Roosting in trees

Elevated perches

Social behaviour

Small groups including cocks

Division into groups, add cocks

Egg laying

Sheltered location

Nest building

Shaded nests

Littered nests (e.g. using chaff)

Comfort behaviour

Dust bathing

Sun bathing

Supply dust bath

Natural lighting

Possible conflict areas

Regulations

The IFOAM standards and the EU regulations contain some sections concerning housing. In

general, the organic standards require that housing conditions must meet the livestock's

normal biological and ethological needs (IFOAM 2002). The animals must be kept in group

housing because they are social living beings. They must have organic material for recreation

and other purposes (e.g. lying on soft ground). Therefore, the housing systems commonly

used in conventional agriculture like tying stalls for cattle, crates for sows, fully slatted pens

for growing cattle or growing pigs and battery cages for laying hens are forbidden.

Furthermore, the animals must have access to outside areas, either to an outdoor run or to

pasture. This offers additional space and contact with climatic stimuli (sun, rain, wind). In

most intensive housing systems, farm animals will never have any access to the outside. The

EU regulation contains minimum space requirements for the stable and the outside area. In

intensive animal production, animals are sometimes mutilated (e.g. beak trimming, tail

docking, teeth clipping, dehorning) to reduce the negative effects of intensive housing condi-

tions. Although the symptoms of intensive housing are removed, the causes remain. In organic

agriculture, mutilations should be avoided or restricted to a minimum (and allowed only as an

exception). However, some people argue that some mutilations are necessary in alternative

housing systems. For example, rooting of pigs at pasture could destroy the vegetation. Nose

ringing reduces pasture damages. However, nose ringing severely hinders the species-specific

behavioural need and could lead to injuries. Feather pecking may be a bigger problem in large

groups of laying hens that are common in alternative housing systems. Beak trimming is a

severe intervention into the physical intactness of the animal. Therefore, appropriate manage-

ment measures are very important to avoid such mutilations in alternative housing systems.

The aforementioned regulations for organic livestock housing offer good preconditions for

animal welfare. They can be regarded, and this should be communicated to consumers, as

strong principles, similar to the ban of pesticides in plant production. Literature on the distri-

bution of housing systems in organic agriculture in different, primarily English-speaking

countries is scarce. However, housing systems seem to differ considerably between countries.

For example, in Austria organic pigs are normally housed indoors with an access to an outside

run (mostly with a solid concrete f floor) for fattening pigs and gestating sows, but not for far-