Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

The presence or absence of sexual reproduction in the pathogen population is

especially significant to the epidemiology of tomato late blight. In temperate zones

where there is a crop-free period, isolates of

P. infestans

adapted to tomatoes are less

certain to survive from one season to the next than are isolates adapted to potatoes.

This is because tomato pathogens have no effective means to survive the inter-

cropping period. Potato pathogens, on the other hand, survive on tubers (in storage,

in fields, or in clamps.) The pathogen appears unable to survive from one season to

the next on tomato seeds, and other parts of the tomato plant typically die between

seasons. Survival of

P

.

infestans

in infected tomato tissue (leaflets, stems, and green

fruits) either kept on the soil surface or buried 10 cm deep, under field conditions in

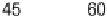

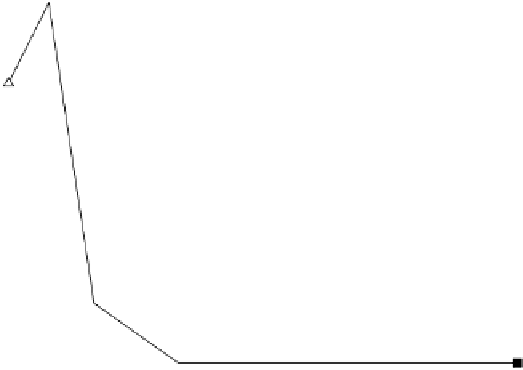

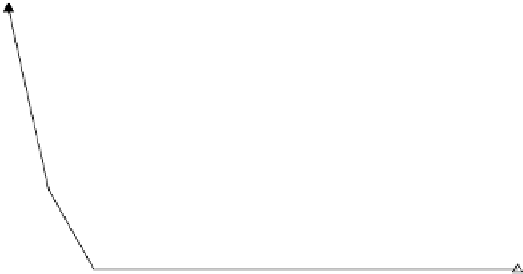

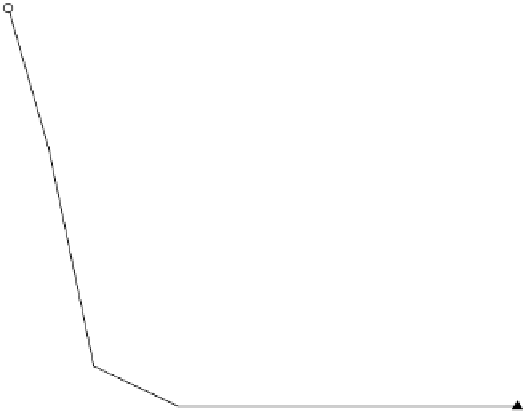

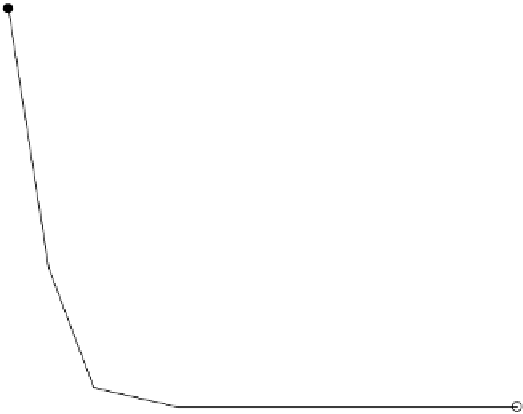

Brazil, was limited. No viable structures were found after 30 days (Fig. 17.1) (M.A.

Lima, L.A. Maffia and E.S.G. Mizubuti, unpublished data).

Figure 17.1. Survival of

Phytophthora infestans

in infected tomato tissues: leaves, stems or

tomato fruit. Samples were kept either buried or on the soil surface, under field conditions

(Spring to Summer) in Brazil. Survival was estimated by periodically sampling infected tissue

and subjecting samples to a bioassay modified from Drenth

et al

. (1995).

There are survival mechanisms even if potatoes are not involved. If hosts of

P. infestans

are growing in a region, these can be a source of the pathogen. In

temperate regions, some glasshouse or greenhouse production can be a source.

Tomatoes are an expected host, but recently it has become clear that petunias and

calibrachoas can also be hosts to

P. infestans

(Becktell

et al

., 2005b)

.

Transplants

produced in one region, transported to and subsequently planted in another can

certainly be a source of the pathogen. In the highland tropics where potatoes are