Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

mandibular shape and feeding biomechanics, and that hyenas are far more protracted in

their development than coyotes (Tanner et al., 2010a;

La Croix et al., 2011a,b

).

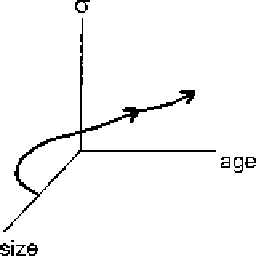

The concept central to all studies of evolving ontogenies is the “ontogenetic trajectory”,

introduced by

Alberch and colleagues (1979)

to signify the complete record of the physical

appearance of the organism. It has been defined as much by an iconic diagram

(

Figure 11.1

) as by words or formula. The diagram depicts a phenotype as a trajectory in a

space of three dimensions: size (s), age (a), and shape (

). Two of these (size and age) are

one-dimensional, but shape obviously is not. When the diagram was initially drawn,

shape was typically characterized by a single ratio but, as explicitly stated by Alberch and

colleagues (p. 299), the picture remains the same no matter how many shape coordinates

are required to specify the system. Now that we have methods for multivariate shape

analysis, we can construct the ontogenetic trajectory for a multidimensional ontogeny of

shape, although in the case we show here (

Figure 11.2

), the piranha Serrasalmus gouldingi,

we do not have any data on age. We thus have only two axes

size and shape. We begin

with this example, despite our lack of data on age, for two reasons. First, many studies do

not have information about age so empirical studies of ontogenetic trajectories are often

restricted to size and shape data, and second, the ontogeny of shape for this case is simple.

By “simple” we mean that the direction of shape change is constant throughout

ontogeny

it is not a function of size (or age). We can therefore represent the ontogeny of

shape by a single vector, and score each individual for its position along it relative to size.

These scores are obtained by projecting the shape data onto a line in the direction of the

ontogenetic shape change, i.e. the vector of regression coefficients when shape is regressed

on log-transformed centroid size (

Drake and Klingenberg, 2008

).

When we have age data, as we do for the cotton rat, Sigmodon fulviventer, we can

include that in the diagram (

Figure 11.3

). This diagram is more difficult to read because it

shows three-dimensions projected onto a two-dimensional plane. To see the relationship

between shape and size, and between shape and age, we can show each pair of axes sepa-

rately (

Figure 11.4A, B

, respectively). As evident in the plot for shape versus size, the rela-

tionship between shape and size is linear but that between shape and age is not. The other

non-linearity is not evident in this plot because the regression vector is obtained by linear

regression of shape on size or age. But the ontogeny of shape changes its direction from

age to age (

Figure 11.5

). In this case, the ontogeny of shape cannot be represented by a

line. Between two ages, such as birth and 10 days, it can be represented by a line, but that

σ

FIGURE 11.1

The ontogenetic trajectory, as depicted by

Alberch et al.,

1979

.