Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

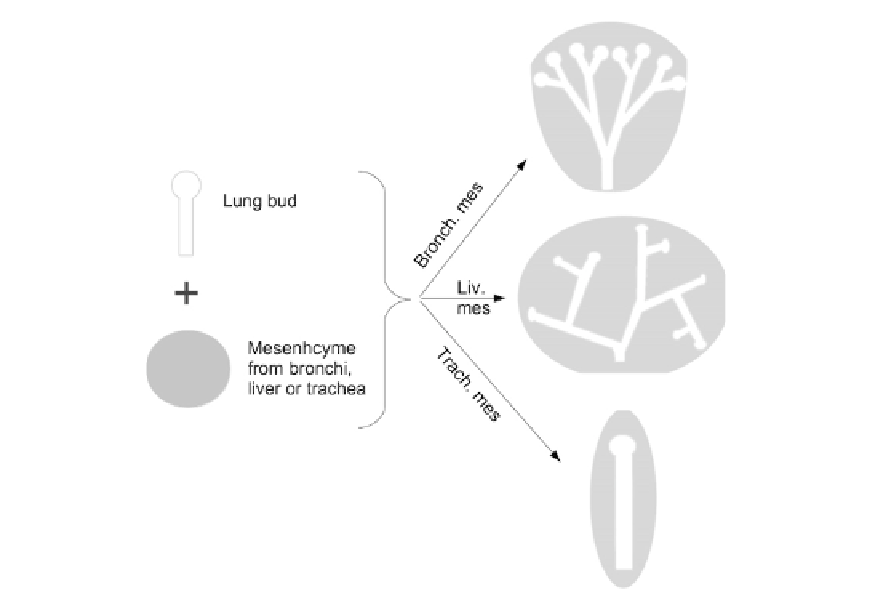

FIGURE 27.2

Diagram summarizing the combined results of two sets of experiments,

7,8

in which a tissue-

engineered chimaeric organ was produced using the epithelial bud of one organ, in this case the lung, and the

mesenchyme of this or another organ. When lung buds are combined with bronchial mesenchyme (their normal

partner), a typical lung branching shape results. When they are combined with liver, a branching pattern similar to

liver bile ducts is seen, whereas when they are combined with tracheal mesenchyme, no branching at all is seen. The

results imply that, at least for these endoderm-derived glandular organs, permission to branch and branch pattern

are controlled mainly by the mesenchyme.

The tissue engineering approach has also provided an excellent way to test a very basic

important hypothesis: that cell behaviour depends on the here-and-now and not on history.

A cell's history can of course determine its state of differentiation and therefore which

morphogenetic machines are present in it; but the morphogenetic behaviour of those

machines is assumed to depend only on the chemical, mechanical and electrical influences

present and not on a long memory of previous events. This hypothesis can be tested by taking

several identical developing embryonic organ rudiments, disassembling them to a simple

cell suspension in which existing positions in the organ and neighbour relations are erased,

bringing the cells together again and seeing what they do. If they organize themselves to

develop a single new organ, then they are clearly capable of forgetting what they were doing

before being disassembled, and responding correctly to their new environment. In other

words, they are capable of adaptive self-organization based on present circumstances. Their

producing one new organ from several cells proves that cells cannot simply return to their

old positions, since more than one cell would have a claim on each position and neighbour

contact.