Database Reference

In-Depth Information

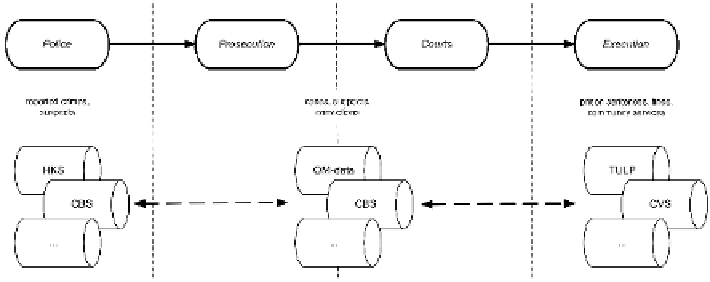

Fig. 10.1

Databases in the Dutch criminal law chain

10.3 Collecting and Combining Judicial Data

The database systems described above have in common that they contain data

about individuals and their actions. Each of these individuals came into contact

with the police or the criminal justice system. Each organization involved registers

privacy-sensitive attributes such as name, address, and identifying numbers, but

also other data regarding a person. The different databases thus store the same, or

similar, information and, therefore, they are partially redundant. Consider, for in-

stance, the database systems of the police and the prosecution service that both

contain data about people who are suspected of a crime and about the crimes they

supposedly committed. If someone is suspected of a murder, both the database of

the police and the database of the prosecution service will contain information re-

garding the date and place where the body is found and (if known) the date and

place where the murder is committed. Other information, however, is registered in

only one of the databases. For example, the police database contains detailed in-

formation about the suspect (such as whether he is first offender or not), while the

database of the prosecution service contains detailed information about the case

(such as the sections of the law that were violated). This is due to the fact that the

police and the organizations involved in the execution of sanctions are individual-

oriented, while the prosecution service and the courts are case-oriented.

To perform their tasks in an effective and efficient manner, the police and jus-

tice organizations not only require access to their own data; they also have a great

demand for a combination of relevant data from other organizations in the crimi-

nal law chain. Organizations with operational tasks (such as the police and the

prosecution service) require combined data at an individual level, while organiza-

tions with strategic or knowledge transfer tasks (such as policymakers and crimi-

nologists) require data at a higher aggregation level.

As an example of the former, assume that a Public Prosecutor wants to prose-

cute a suspect for his actions, then all relevant data (from different sources) that

pertain to this suspect should be collected and combined. In this way, the prosecu-

tor can build the strongest case possible, because all information about the suspect

is gathered; including evidence for the fact that he is a criminal. Thus, integrating

Search WWH ::

Custom Search