Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

Story

Game

End

End

Start

Start

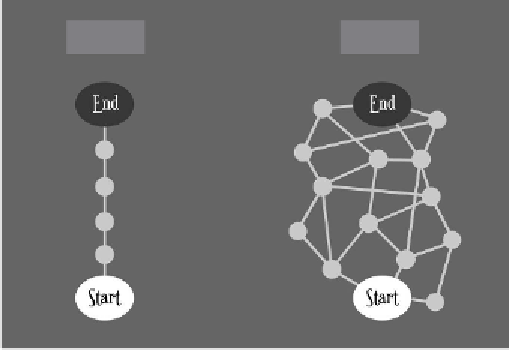

Figure 7

. A rough representation of the shape of a story versus that of a game.

various events. I need to make clear that I'm by no means saying that

stories are simpler than games. Both stories and games are complex

“machines� that actually have to function, each in their own way. Good

stories have many threads that interweave with each other in a grace-

ful and beautiful way. In terms of what the user experiences, they are

right). The experience is more like a constantly evolving and emerging

web, since as players go through them, the nodes and connections (the

possibilities and choices) are changing. It's not always clear to players

how nodes are connected—in fact, getting better at a game is a process

of getting better at predicting the future structure of the web. When we

can completely map out the entire web of a game (as we can do with any

story we've seen before), the game actually is “solved� and becomes use-

less to us (think tic-tac-toe, in which most adults know with certainty the

optimal move in any situation). So those who are interested in making a

story-based game essentially are left with the three options below.

Cutscenes.

he most common way to create story-based games

is to use cutscenes. With this method the application essentially

bounces back and forth between a movie and allowing the user to

play the game parts. It has become more clear to most develop-

ers that this method is a somewhat sloppy solution and players

will probably grow more and more irritated by it as time goes on,

since having a play experience interrupted is frustrating.

Metal