Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

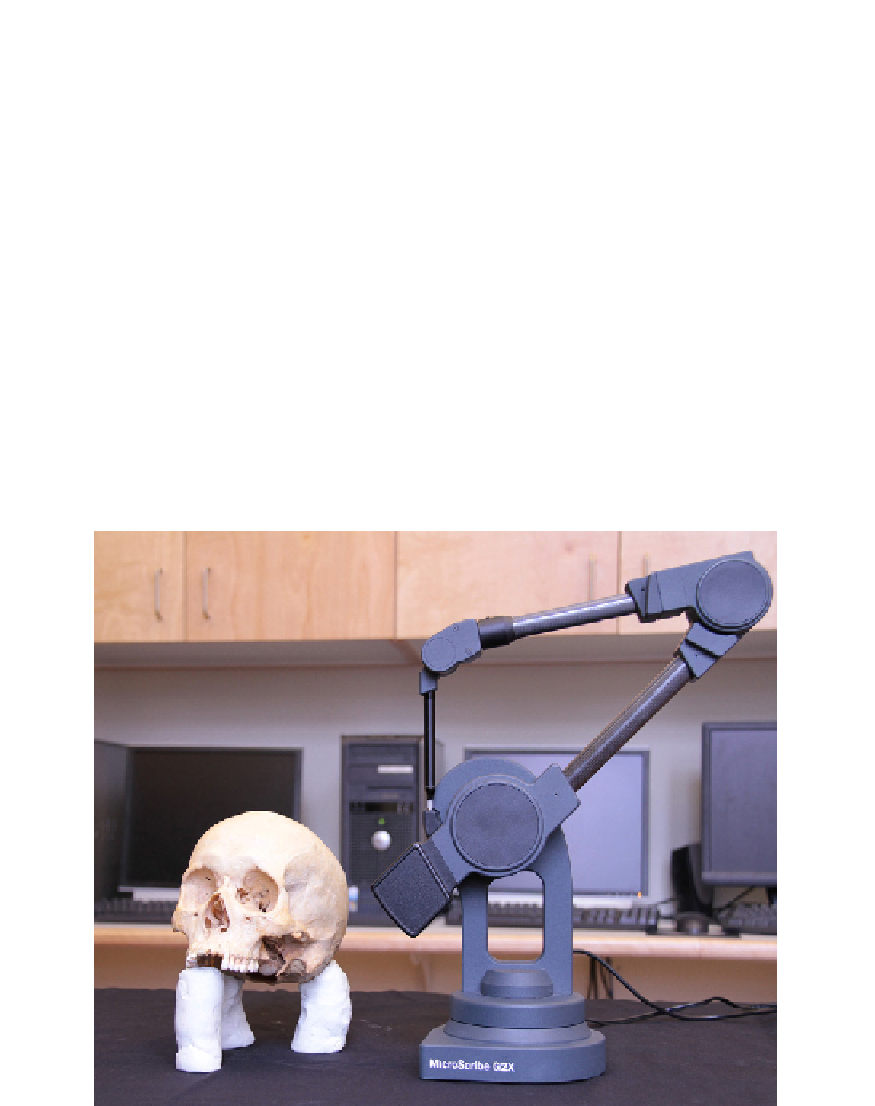

immobile during the digitizing process. This keeps the landmark coordinates for each spec-

imen in the same coordinate system as a coherent configuration. The need for the specimen

and digitizer to be stationary requires securing the cranium, skeletal element, or two-dimen-

sional image such that all landmarks or structures to be traced are accessible. When working

with dry bone specimens, they must be placed in a stable and secure configuration, as the

safety of the skeletal material is a critical consideration.

Figure 12.3

shows a cranium posi-

tioned for digitizing with a Microscribe or Polhemus. All landmarks can be reached with

the stylus tip and the arcs can be traced without interruption. A mirror can be used to facil-

itate tracing the occipital arc.

Laser scanners do not have the same restrictions; here the specimen is typically placed on

a platform that rotates and all observable surfaces are scanned. The specimen often needs to

be repositioned and rescanned, so that all surfaces are captured. Computer software

programs associated with the laser scanners then “stitch” the scans together to produce

three-dimensional renderings of the entire specimen.

The observation of landmark coordinates is subject to error due to inaccurate identification

of landmark location (lack of precision) and variation among observers (lack of repeatability).

Several studies (

Corner et al., 1992; Richtsmeier et al., 1995; Aldridge et al., 2005; Ross and

FIGURE 12.3

Cranium positioned for data collection with a three-dimensional digitizer. Photograph by Roselyn

Campbell.