Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

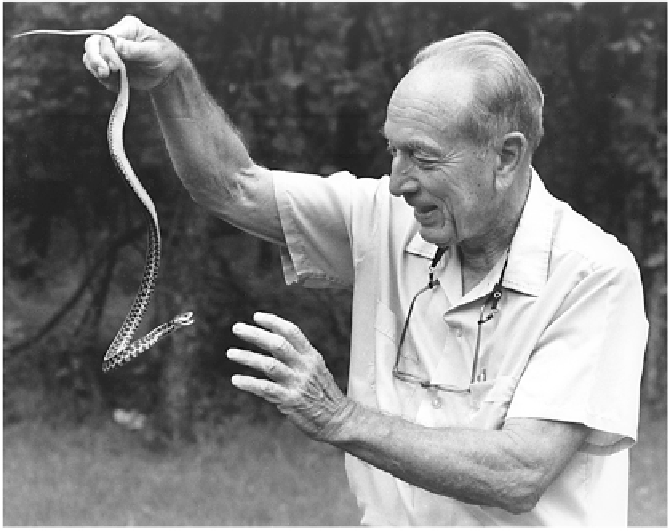

Henry Fitch in 1991, trim and fit at age eighty-one, examining a common gartersnake, Fitch Nat-

ural History Reservation, Douglas County, Kansas. (Photo: V. Snider)

On the K.U. campus that night, Henry sat in the front row for my lecture titled “Her-

oes, Theories, and Organisms as the Central Focus of Biology.” I held aloft his fifty-year

study,

AKansasSnakeCommunity,

and summarized the man's phenomenal legacy of an-

imals marked and measured, stomach and scat contents tallied, and papers published.

13

Henry had bridged the descriptive natural history of Wallace and Darwin, I explained,

in what amounted to three careers, counting the San Joaquin Experimental Range, K.U.

Natural History Reservation, and tropical expeditions. In fact, although best known as

a herpetologist, he'd made contributions to mammalogy exceeding those of many nom-

inal mammalogists. During my talk, to exemplify the importance of field observations

for generating new research opportunities, I described island cottonmouths feeding on

with head tilted down and a slight swing of the chin, he added with a chuckle, “Oh, and

thanks for the plug!”

A prairie moon glowed through low, heavy fog as I drove back to town after taking

Henry home; orange lightning flashed over fields and hedgerows while I wondered

anew,

What makes him tick?

Years ago, when I'd complained about scarce funding,

he replied, “I've always spent time on whatever interested me most—with or without

grants—and have greatly enjoyed all my projects, especially the fieldwork.” More re-

cently he told the author of a topic on Kansas personalities, “I wouldn't change a thing.

People who work with animals in the field, whether snakes or birds or rodents or mon-

keys, find it deeply satisfying and wouldn't trade it for any other career—even though