Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

There is a saying in the game industry that originated from industry pioneer Sid

Meier. He suggested, “A game is a series of interesting choices.� That statement is,

in my opinion, reasonable in a vague sense. However, with a little exploration, you

can bracket things a little better. For example, if you were to pursue that concept by

negation to the extreme, you would be left with the statement, “If there are no

choices for the player, it is not a game.� That is certainly true. What would be left

is the monodirectional narrative that games have been replacing for decades now.

Aside from the initial choice of what to watch, television and movies do not provide

choices for the viewer. They are not interactive. They are not games.

Topics have historically fallen into the same category. The exception to this is

the “choose your own adventure� topics. Unlike typical narratives, they allow the

reader to make choices that, while very simple, do affect the outcome of the story.

It is the addition of that simple mechanism that lifts the topic from narrative enter-

tainment into the realm of interactive entertainment. And, if the alternate paths

and endings were divergent enough to be construed as “positive� or “negative,� one

could make the case that there is now a goal—and a corresponding concept of

“winning� and “losing.� In a sense, the topic has now become a game.

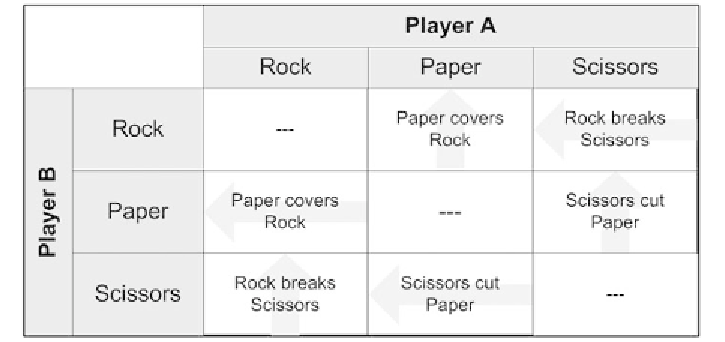

Rock-Paper-Scissors, the staple mechanism of alleviating sheer boredom and

selecting hapless people for distasteful tasks, has but one choice event with three

possible selections in any given round (Figure 1.1). Flick the fingers, and you are

done. All that is left is to count the score. That hardly makes for long-term enter-

tainment. (In fact, it may be disqualified from consideration in Sid's definition in

that there isn't even really a

series

of choices.)

FIGURE 1.1

The decision matrix for the game Rock-Paper-Scissors.