Game Development Reference

In-Depth Information

When Is Dying not Dying?

One of the more famous examples showing how people's decisions can be greatly

affected by their perceptions was offered up by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

Incidentally, despite being a psychologist, Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in

economics in 2002. (Tversky had died a few years prior to that; otherwise he would

have been the co-recipient.) The point is that there is an increasingly significant and

accepted link between psychology and the realm of economics.

In their experiment, they presented the following choice to one group of people:

Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian

disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to

combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific

estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

If program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

If program B is adopted, there is a

1

â?„

3

probability that 600 people

will be saved and a

2

â?„

3

probability that no people will be saved.

Which of the two programs would you favor?

Additionally, they presented the same scenario to a second group of

people but with different choices:

If program C is adopted, 400 people will die.

If program D is adopted, there is a

1

â?„

3

probability that nobody

will die, and a

2

â?„

3

probability that 600 people will die.

Which of the two programs would you favor?

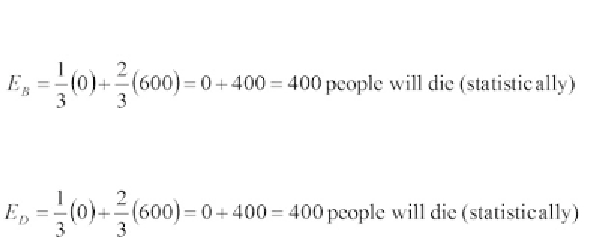

It may take a bit of looking at the question, and maybe a pencil and paper, but

closer examination shows that the choice between A and B is the same as the choice

between C and D. If we were to show the various choices in terms of expected

deaths

, without regard to wording, we are able to cut through the clutter somewhat.