what-when-how

In Depth Tutorials and Information

CERVICAL SPINE

with treatment with halter traction and cervical collar

in the case reported by Rush.

33

It is obviously of great

concern that these individuals may develop cord com-

pression over time and require operative treatment, but

there is no guidance from the literature as to the opti-

mal treatment of this abnormality in patients with OI.

Paraplegia after chiropractic manipulation has also

been reported.

11

The cervical spine can obviously be involved with

subtle fractures, instability and cranial settling. The

treating physician must be acutely aware of the cranio-

cervical abnormalities that occur in OI, which are

covered in another chapter of this topic. This is espe-

cially true if the need for anesthesia is anticipated.

Stabilization of the neck by the surgeon at the time of

intubation and positioning in all patients is important

to prevent injury to the spinal cord, as many of these

abnormalities may be undiagnosed. Vertebral body

fractures can obviously occur in OI but in clinical prac-

tice, symptomatic or obvious cervical abnormalities

are less common than thoracic or lumbar fractures in

the authors' observation. The one fracture pattern that

has been noted in our clinic population in two patients

is a fracture or congenital abnormality of the posterior

elements of C2 or Hangman's fracture. One of these

patients with type III OI initially presented as a dys-

plastic elongation of the pars at age 2 years, 11 months

of age. He was treated with a cervical collar but by age

3 years, 10 months had a clear-cut lysis though remains

asymptomatic (

Figure 44.7A, B

). The second patient in

our clinic presented with an absence of the lateral mass

of C2 at 6 months of age and also continues to be asymp-

tomatic (

Figure 44.8A, B

).

Three-dimensional CT (

Figure 44.8C, D

) scan veri-

ies the space between the lamina and body of C2 with

absence of the lateral mass. A similar fracture healed

SPONDYLOLYSIS AND

SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis of

the vertebrae. This typically occurs in the lower lumbar

spine, most commonly at L5-S1 because of the increased

stress on the posterior elements due to lordotic posture

at that level (

Figure 44.9

). It does not typically occur in

individuals who do not ambulate. There are a variety of

classifications of spondylolysis.

34,35

The most common

type seen in OI is isthmic, which is felt to be secondary

to multiple repetitive stresses on a potentially predis-

posed individual (

Figure 44.10

). It is also more common

in individuals who perform repetitive hyperextension

activities. The second type that is most commonly seen

in OI patients is the dysplastic type.

34,35

This is caused by

an elongated, abnormally formed pars, which therefore

is weaker and more prone to failure. In OI, the predispo-

sition to spondylolysis may be related to a combination

of both factors (

Figure 44.11

).

36

It is also common to see

elongated pedicles, especially in patients with the more

severe types of OI, such as type III (

Figure 44.12

).

17,37-39

The incidence of spondylolysis in the normal popula-

tion has been reported to be 4.4% in the pediatric pop-

ulation, increasing to about 6% by adulthood.

34,35,40-43

Spondylolisthesis is described and defined as a forward

slippage of the vertebral body onto the vertebral body

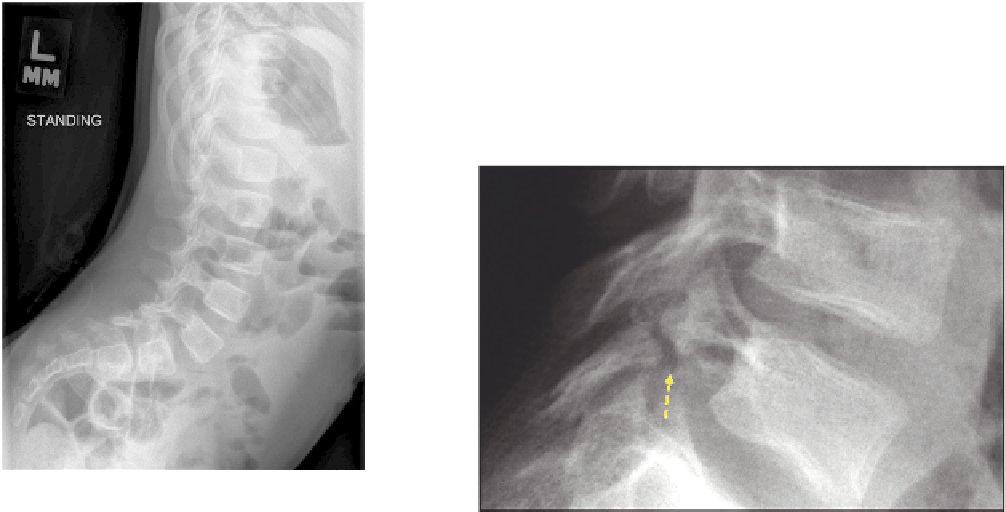

FIGURE 44.9

Four-year-old with type IV OI with the increased

lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt seen in many ambulatory chil-

dren with OI. Note also the elongation of the lumbar pedicles and

pars with mild listhesis of L5 on S1.

FIGURE 44.10

Isthmic spondylolysis.