what-when-how

In Depth Tutorials and Information

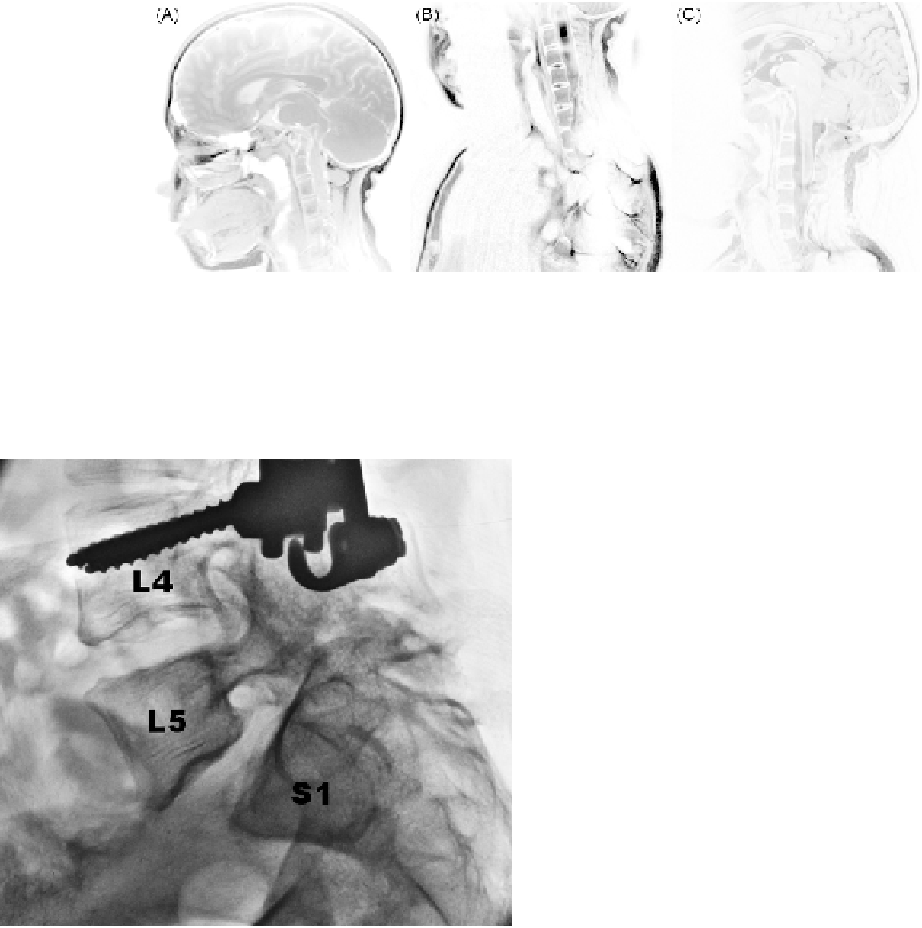

FIGURE 43.1

MRI images showing the pathology of an OI patient with basilar invagination. (A) Preoperative sagittal T1-weighted image

shows evidence of basilar invagination, narrowing of the foramen magnum, and compression of the anterior surface of the medulla oblongata

resulting in neurologic symptoms on examination. (B) Preoperative sagittal T2-weighted image demonstrates a multiloculated syringomyelia

in the cervical cord extending from C2 through at least C6. (C) Following upper cervical laminectomy with dorsal occipitocervical fusion, this

T2-weighted image demonstrates resection of the anterior arch of C1 and partial resection of the body of C2 (odontoid process) with relief of the

cord compression.

the vertebra below, usually following spondylolysis.

Both conditions are typically found in the lower lum-

bar spine, a direct result of increased stress on the pos-

terior elements of the lordotic spine. Deformation of the

bone from the increasing mechanical load that naturally

occurs during childhood can cause rapid progression of

hyperlordosis and pedicle elongation resulting in spon-

dylolisthesis and spondylolysis.

9,10

Although there have been many case reports and iso-

lated findings, the incidences of spondylolysis and spon-

dylolisthesis have not been frequently estimated in the

literature. The few studies that investigated these con-

ditions have demonstrated higher prevalences of these

conditions in OI patients as compared to the general pop-

ulation. A study by Hatz et al. observed a spondylolysis

incidence of 8.2% and a spondylolisthesis incidence of

10.9% in pediatric OI patients.

11

As a comparison, normal

children below the age of 6 have a spondylolysis inci-

dence of 4.4%, which increases to 6% in the adult popula-

tion.

12

Spondylolisthesis incidences range from less than

3% in children to 6-8% in adults.

13

The Hatz study noted that their observed incidence

of spondylolysis was higher than a reported figure of

5.3% in a study by Verra et al. Interestingly, 79% of the

patients included in the Hatz study were capable of

holding themselves upright to some degree, which con-

trasted with the Verra study, where none of the patients

were capable of ambulation or significant physical activ-

ity. This suggests that OI patients who are capable of

ambulating are more prone to developing spondyloly-

sis and spondylolisthesis. This is most likely a result of

an increased load-bearing requirement of the lumbar

spine in ambulating patients. Lastly, Hatz qualitatively

observed that many of the ambulatory patients included

in the study had increased pelvic incidence and hip con-

tractures, which can lead to further stress on the lumbar

spine.

11,14

FIGURE 43.2

OI patient with spondylolisthesis. One can observe

anterior subluxation of L5 on S1. Pedicle screws from the fusion con-

struct are seen in L4.

The subject of craniocervical junction abnormalities

is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 36 (see Basilar

Invagination), which includes further information on

diagnosis and treatment.

SPONDYLOLISTHESIS AND

SPONDYLOLYSIS

Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis are spinal con-

ditions that are relatively unique to bipedal ambulators.

Spondylolysis is a defect or break in the pars interar-

ticularis of a vertebra. Spondylolisthesis (

Figure 43.2

)

is the forward movement of one vertebra relative to