If you’ve ever read through the Alias manuals, you may remember this line: “Maya is nodes with attributes that are connected.” It keeps coming up again and again due to its importance in defining the way the software works. It also bears mentioning that there are often a few different terms used to convey the same concepts.

One example of this is the word Channel. A channel is really no different than a keyable attribute. Maya’s nodes are filled with both keyable and non-keyable attributes. For any given node, the Channel Box (see Figure 2.1) is the list of the most commonly keyframed attributes. The Channel Box gives you access to these values, and it allows you to change and set keyframes for them.

Also present in the Channel Box are the nodes to which the model is connected. Here is a simple example. The Transform node is the top node of an object. The Transform node defines the movement, rotation, and scale of an object. Below that is the Shape node, which stores information about the physical appearance of an object (such as vertex tweaks). At the bottom of the Channel Box are the Input nodes. These represent the initial creation of the object, as well as other operations that have been applied. If you were to change one of these Input node attributes, such as Radius or End Sweep of a NURBS sphere, you would see the object change just as if you had originally created the sphere with those attributes.

Figure 2.1: The Channel Box and Perspective Panel

The Outliner

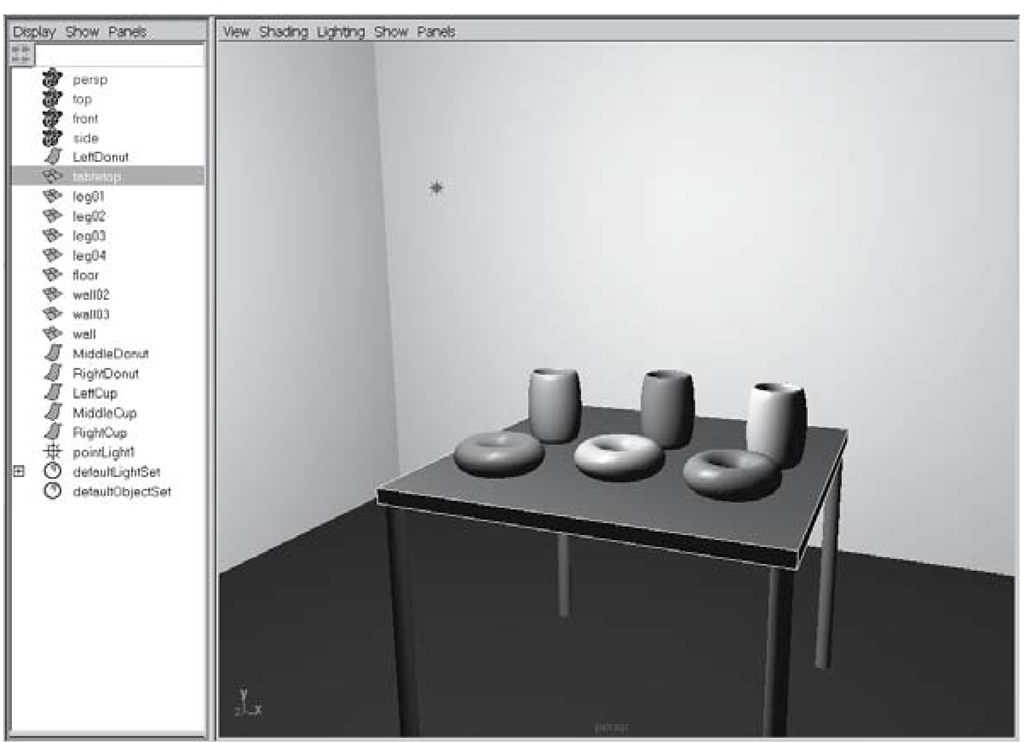

As you have already seen, the Maya workspace has many different ways of presenting information about the objects in your scene. One such way is the Outliner. At its most basic, the Outliner is a list of the objects in your scene. Select Window > Outliner . . . to open up a new Outliner window.

In the scene shown in Figure 2.2, we can see that the Outliner lists the four viewports, the primitive objects, the point light, and the default light and shader sets. Note that the small icons help you to identify the type of object. For example, the NURBS primitives have a small patch icon, while the polygon plane primitive has a more grid-like icon.

Figure 2.2: The Outliner and Perspective Panel

Try picking objects in the Outliner and watch as they are selected in the perspective panel. This can be very helpful in complex scenes where direct object selection is difficult. There are other uses for the Outliner which we will explore in later lessons, but for now you’ll use it for picking objects.

Keyboard Shortcuts for Transformations

The transform tools and their corresponding locators are a necessity when it comes to doing much of anything within the Maya workspace. They’re so important that they have their own set of convenient keyboard shortcuts. This way you don’t have to select them in the toolbox every time you want to change among selecting, moving, rotating, and scaling modes. The keyboard shortcuts are QWERTY.

These manipulators all allow you to constrain your operation along a specific axis:

• Red = X axis;

• Green = Y axis;

• Blue = Z axis;

Yellow represents the currently selected axis. For two-axis translation, you can ctrl+ LMB click an axis to remove it from the constraint set, thereby limiting the operation to the other two axes. This can be especially useful when animating an object while working in a perspective or camera panel.

Project and File Management

Project and file management can be one of the most important aspects of making a production run smoothly. Keeping track of the scenes, source images, textures, sound files, custom UI elements, and rendered images can be a real chore. Maya has a default file structure to aid your organization of these assets.

Whenever you start a new project (see Figure 2.3), you should go to the File > Project > New… menu to create a new directory structure.

Name your project (see Figure 2.4) and then accept the default settings, and Maya will create a new project directory with a series of subdirectories. This is where Maya will go to save scenes, browse for textures, and output rendered images.

Think of the project in these terms: your Maya scene (.ma, .mb) contains geometry, animation, lights, material, and other information that you create inside Maya. Scenes are stored in the scenes directory of your project.

All elements created outside Maya — such as textures you have painted in Photoshop or audio files for synching with your animation — need a place to reside that your scene can easily find. The project directory structure has a sourceimages directory for your textures (.jpg, .tga, .iff, .bmp, etc.), a sound directory for your audio (.wav, .aiff), and so on. You establish a relationship between your scene and these elements, but it is never anything more than a link between two elements. Your texture and sound files are never embedded into your scene file; they are merely pointed at. This is why the path established using the project directory structure is so important (see Figure 2.5). If an element is moved or deleted from the directory your Maya scene expects to find it in, you’ll get an error, and the scene may not render correctly.

Figure 2.3: New project

Figure 2.4: Project naming

Figure 2.5: Project directories

Even things that are output from your Maya scene, such as rendered frames, need a home. For this, the project contains an images directory. Here, you’ll find your finished frames after an animation has been batch rendered.

Here is an example of file management in action. Let’s say you are beginning work on a short film entitled “The Chicken Farm.” First you would launch Maya, and then click File > Project > New. to bring up the New Project window. You could name the project ChickenFarm, and then choose the path where you would like the project stored. (The default is in your user account’s maya/projects directory.) Next, click the Use Defaults button, to automatically name the directories where different project elements will be stored. Click the Accept button. This tells your operating system to build the set of directories needed.

Now, if you sketch some concepts for your character, paint some textures, or create model sheets, they can all be saved into the ChickenFarm/sourceimages directory. When you record a dialog track, it can be saved into the ChickenFarm/sounds directory. In Maya, when you begin working on the first scene, you will click File > Project > Set. Browse to the ChickenFarm project and click OK. When you then save your scene, the ChickenFarm/scenes directory will automatically be chosen as your save directory. If you need to import your character sketches for reference, the ChickenFarm/sourceimages directory will be selected. When you need to place your audio file into the timeline, the correct directory will open first. Finally, when you render the animation, Maya will send your finished frames to the proper ChickenFarm/images directory.